The Impact of the Reformation

The Impact of the Reformation

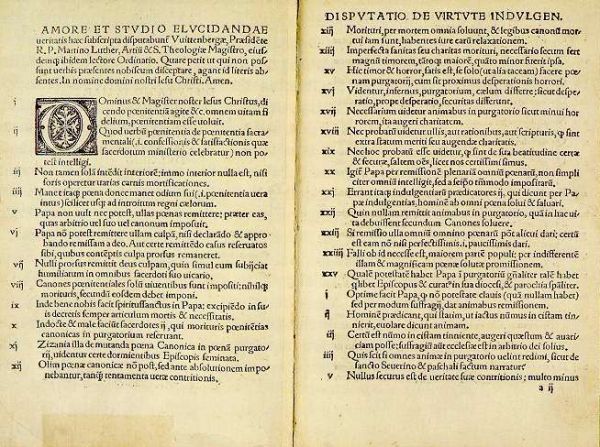

An early copy of Luther's 95 Theses in the original Latin.

I have studied the history of Germany in the period leading up the Reformation, and wondered why the Reformation took so long to get rolling? Informed people knew that corruption, nepotism, and greed fed the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church—more or less like the biblical history of the Israelites, or any other great human institution, for that matter: Its leaders progressed from exploiting the perks of their offices to actually perverting the intentions of that office; but it happened gradually so that fes noticed it.

In the play Luther by John Osborne, the title character Martin Luther watched as Dominican monks offered religious trinkets—called "Indulgences"—for sale and claimed that their trinkets granted to the buyer forgivenesss of sins. They claimed that no sin was too big to grant the buyer forgiveness, provided the buyer paid all he could for the trinkets. So Luther asked his congregation, "There are some who complain about these things, but they write in Latin for scholars. Who will speak out in rough German? Someone's got to bell the cat."

So Luther decided he himself would "bell the cat". (Hang a bell around the cat's neck to warn the mice.) So finally, someone decided to act! Martin Luther risked imprisonment and even execution by the enforcement arm of the Papacy. On October 31, 1517, he tacked his 95 Theses onto the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, and the ball started rolling. People came to the Wittenberg Door—located on the north porch—to copy down the Theses, then carry the text of them to a printer. Without Luther's knowledge, printed copies of the Theses spread across Europe. Within a year, Thomas More, the "High Chancellor" under the English King Henry VIII had seen them.

But besides tackling the corruption, commercialism, and nepotism in the Papacy, the Reformation challenged people to think differently about themselves. In his book, Luther: Out of the Storm, for instance, Derek Wilson writes that the Reformation succeeded because "the psychological climate was very right." Wilson continues:

One way to gauge it is in the demeanour of worshippers. A modern Catholic historian laments the growth of individualistic lay piety and its undermining of the sacramental liturgy. . . . The religion of the laity came to consist more and more in their personal relations with God.

Later in his book, Wilson returns to this theme:

Modern readers may find it difficult to grasp just how moving and liberating this advocacy of personal, affective religion could be to hearers accustomed to exhortations to cling to the skirts of mother church as the only way of avoiding the eternal torments of hell.

In the Osborne play Luther, Luther locks horns with the Pope's representative Cardinal de Veo, aka "Cajetan":

Cajetan: My son, you have upset all Germany with your dispute about indulgences. . . . All you are required to do is to confess your errors and keep a strict watch on your words.

Martin: But I'm asking you to tell me where I have erred.

Cajetan: Here are two propositions you have advanced which you will have to retract:

First, indulgences do not consist of the sufferings of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Second, the man who received the Holy Sacrament must have faith in the grace that is

presented to him.

Martin: I rest my case entirely on Scriptures.

Cajetan: The Pope alone has power and authority over all those things.

Martin: Except Scripture.

Cajetan: What do you mean?

And there you have perhaps the most important alteration caused by the Reformation: an authority superior to the Pope. The Church had operated up to that point with a human interpreter of the Will of God. The reformers—all of them, Knox, Zwingli, Luther, and Calvin—considered Scripture the definer of the Lord's Will.

In Scripture, one finds the time-tested, unvarnished history of Mankind in the making—lessons from raw human experience— people in positions of power; their dishonesty and hypocrisy laid out for all to see. In any serious study of Scripture, you cannot miss how pessimism imbues the telling of the stories.

Stay tuned for my third post on Martin Luther.