The Jewish-Communist Goebbels

William Sheridan Allen was a history professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He served in that capacity until 2001 and passed away in 2013 at age 80. In 1965, he published The Nazi Seizure of Power, which sold so well, he revised it and reissued it in 1984.

To prepare for his task, Professor Allen made a few preliminary arrangements. He approached the city-leaders of Northeim, Germany, (pronounced "Nort-hyme") located in Lower Saxony, and asked if he could consult the city's historical archives, starting in the early-1930s, leading up to the victory of the Nazi Party, the establishment of the Nazi dictatorship under Adolf Hitler, and ending with Germany's defeat at the end of World War II.

The city-leaders of Northeim gave their assent, asking only that Allen conceal the city's identity, as well as the names of the people who lived there; so Allen gave them all a pseudonym. With that agreement settled, Allen started to work. Instead of Northeim, Allen gave it the name "Thalburg". For the local Nazi leader in Northeim, Ernst Girmann, Allen gave him the pseudonym "Kurt Aergeyz", pronounced like "Ehrgeiz", the pejorative German word for "ambition". Allen also gave Girmann's opponent in the Socialist Party, Karl Querfurt, a pseudonym, "Karl Hengst". "Hengst" is the German word for "stallion", which suited the courageous Querfurt perfectly. His courage landed him in prison on more than one occasion. But Girmann and Querfurt had grown up in the same poor, working-class environment and knew each other. Girmann respected Querfurt, which protected Querfurt from the usual fate of socialists in Nazi Germany.

But the German news magazine Der Spiegel, which also read Allen's book, recognized the location and description of the fictional "Thalburg", put two and two together, and gave away Northeim's identity. Disappointed, Allen reissued the book with the names that Der Spiegel had revealed.

I bring up Professor Allen's book because he made an astute observation about voting patterns in Northeim, a city of about 10,000 before World War II. In an election before the Nazi takeover, virtually the same number of citizens who had voted for the Communist Party in the previous election voted Nazi in the next. Allen deduced that the Communist voters must have traded in their loyalty and voted for the Nazi Party. Adolf Hitler himself had once admitted he could never convert a Socialist or a Christian Democrat, but a Communist--no problem!

Additionally, Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, admitted in his diaries "Ich bin ein deutscher Kommunist."--"I am a German communist." This really surprised me--a Communist turning around and voting for the party of the arch-enemy. It seemed counter-intuitive. Der Spiegel ran excerpts from the diaries, where Goebbels explained his reasoning. The Spiegel article said about him, "Goebbels needed the power of someone else to give him a feeling of power. "Je größer und ragender ich Gott mache, desto größer bin ich selbst." In English, "The more power I give my god, the more powerful I become!"

Not too surprisingly, Goebbels made one more startling admission, "Meine Waffe heißt Adolf Hitler!" In English, "My weapon is Adolf Hitler!" The small, slightly-built Goebbels, burdened from childhood with infantile paralysis, wanted to feel powerful, just like any person who sides with a dictator. Imagine though--not Hitler wielding Goebbels, but the opposite, Goebbels using Hitler as his weapon of revenge!

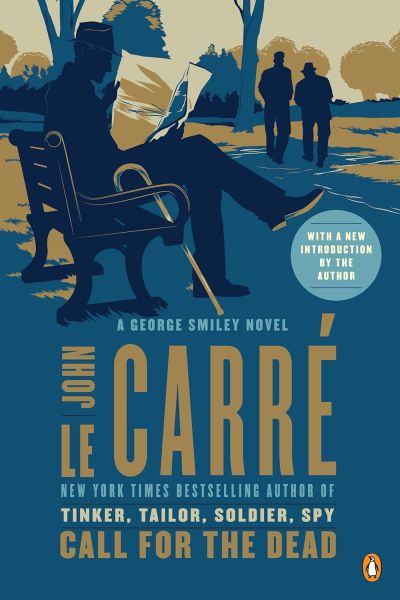

It reminds me of the John le Carré novel, Call for the Dead, published by le Carré in 1961. Call for the Dead tells the story of Dieter Frei, a German-Communist Jew who is running a secret agent. When the reader finally meets Dieter, he is in a theatre to meet his agent. He immediately awes the British spy-catchers who are there to take him into custody, and to top it all off, Dieter has suffered his whole life from infantile paralysis:

As he walked, thrusting his good leg forward, there was a defiance, a command that could not go unheeded. . . . He had not changed. He was the same improbable

romantic with the magic of a charlatan . . . implacable of purpose, satanic in fulfillment. . . .

Dieter was out of proportion, his cunning, his conceit . . . all were larger than life. . . . He thought and acted in absolute terms, without patience or compromise.

I wouldn't be a bit surprised if le Carré patterned Dieter Frei after Goebbels.