The Liberal Church Monarch

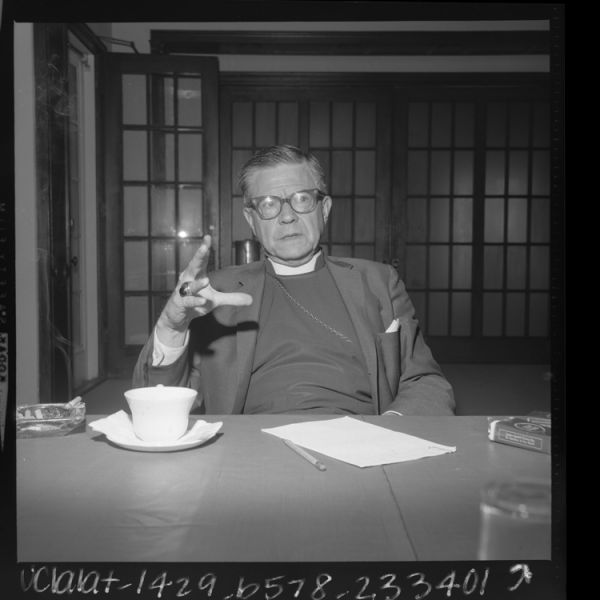

Bishop James A. Pike

Lord Acton: "Despotic power is always accompanied by corruption of morality."

In my post from 19 July, I wrote about a despot, the British King Henry II, and his predilection for teenaged girls, who called him "my Lord" even as he made love to them. Thomas of Becket tried to keep church law beyond the reach of the despotic king and to shield church personnel from secular authority. In so doing, he inadvertently helped modern church personnel evade civil law when they revealed their predilection for young boys. Hundreds of priests and lay-personnel went to prison for their crimes against juveniles.

I would therefore change Lord Acton's "despotic" dictum—and substitute "imperial" for "despotic." An institution does not need despotic power, just imperial power—an accepted level of influence or vested authority, secular or religious—to function above the law. In our divided society, politicians have a good chance of getting away with "corrupt" behavior even today, enabled by party-faithful. The opposing party cries foul to no avail. The party-faithful react with cynicism toward politically-motivated moral outrage. They've heard it all before.

James Pike started attending the Episcopal Church in the 1940s, He attended seminary from 1946 to 1951, worked at Episcopal churches, then accepted the position of Dean at St. John the Divine, the Episcopal cathedral in New York City, in 1952. From there, Pike returned to California to serve as Bishop in San Francisco. Unlike the Catholic Church, a bishop's election in the Episcopal Church results from rather obvious politicking—more or less like the secular world.

Pike pioneered the attitude of a countercultural clergyman, sounding off provocatively on important issues like ordaining women and homosexuals, opposing the War in Vietnam, speaking in support of the Civil Rights Movement, and the integration of schools. Pike wore a doozy of a cross around his neck—a Peace-cross attached to his Christian-cross. Dressed in civvies for an interview, he wore a pink tie with a Peace-cross motif.

His recklessly provocative rantings divided parishes everywhere. Conservatives considered him an out-and-out heretic or disguised unbeliever; Liberals flocked to hear him wherever he happened to touch down. "Jesus was a revolutionary like the Viet Cong!" he exclaimed in a sermon delivered in New York City in April, 1965. He titled his sermon, "The God of Law and Order is Dead."

Liberals fell over themselves, amazed by the balls of this guy. The conservative bishops started to work on some kind of censure and cast about for allies. With each Pike appearance, they added his self-incriminating statements to their growing dossier. His thumbing his nose at the Establishment, rather than stepping away from it, suggests something else more important for Liberals, secular or church Liberals, a sort of acknowledgement that self-doubt inhibits their stepping away from the Establishment. Their spitefulness reflects a frustration over this inability.

Under pressure, Pike eventually resigned as bishop and left the Episcopal Church. He died in 1969 in the desert near Wadi Qumran, not far from the location of the Dead Sea Scrolls, unable to find a sense of direction apart from the Establishment.

Like Thomas of Becket, Pike's influence really took hold posthumously; so that the ordination of Gays and women today in the Epsicopal clergy causes barely a ripple. His sometimes zany left-wing views have also taken hold and define the Episcopal Church at the national level—this one-time arch-conservative organization, the flag-ship of conservative organizations, subverted by the Left. Leftists could create their own church or religion, or their own Establishment; but they prefer the credibility of the existing one, as an avenue to their own success, as a reflection of their own values.

At age 69, I have known a lot of left-wingers like Pike. They use a left-wing stance as a self-definer rather than as a key to innovative thinking, or a spur to pro-active problem-solving. The sameness in their thinking reminds me of a cookie-cutter—the last cookie looking just like the first.

Christians generally know more about the Epistles of Paul, than the Gospels. The doctrinal talking-points of the average Christian start with Paul, rather than Jesus, who deals with relationships more than the founding and definition of an organization; so liberal Christians get doctrinal inculcation twice—as Christians and as Liberals. A sound doctrine makes a sound sleeper! Not someone able to think pro-actively.

I have known liberal Christians for thirty years or more. Their view of things has not changed much in that length of time. This is a point Americans need to consider, if they want to relieve the impasse to national unity.

Pike as Monarch

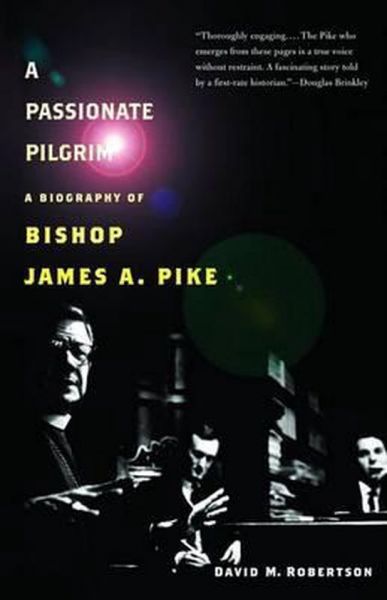

A biography of Pike appeared in 2004, titled A Passionate Pilgrim, written by historian David M. Robertson. It was the first biography of Pike since The Death and Life of Bishop Pike, published in 1976 by William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne. Robertson makes use of previously unreleased material that describes Pike as an expansively monarchical clergyman, expecting the perks typical for a man of his ilk.

Robertson reports on a confidential committee convened by the House of Bishops:

Page 108: Pike signed, in approval, the committee's remarkably foresighted final conclusions,

including the assertion, "When we elect a president of the United States . . . we do not ask him

what he does with his genitals. We want him to do what he is hired to do. We tacitly agree that his

sex life is his own affair."

The committee's report was kept at its request from most Episcopal laity on a 'need to know' basis.

Considering all that Pike did during his career as a churchman, he must have led the "confidential committee" by the nose. This gag-rule, passed down by leading churchmen, would have suited him perfectly. In fact, the public expects moral standards from its leaders, not just professional ability, which explains the need to keep the committee's report secret.

Page 107: "Rumors of marital infidelity were repeated more frequently after the family moved

to San Francisco. "It was a constant whisper in the diocese," Darby Betts recalled.

Also that year, Pike invited Betts to move to San Francisco and become the archdeacon of the

diocese. . . . Betts accepted the offer, but discovered soon after his arrival that his unspecified

duties included acting as a majordomo to Pike, attempting to prevent the bishop from publicly

embarrassing himself with women or alcohol.

Bishop Pike's face appeared on the cover of Time magazine on November 11, 1966. The article on him was mostly favorable and contained a photograph of the smiling Bishop and his wife Esther. It touched only lightly on the Bishop's personal problems.

Robertson fills in the content-gaps mercilessly:

Page 176: The same month as the article appeared, Pike and Diane Kennedy had become physical

lovers. She remained in the San Francisco area, and he saw her intermittently.

He was, in effect, supporting three households—his own with [Maren] Bergrud [Pike's live-in

girlfriend] in Santa Barbara; the apartment he also maintained in her name and used as an office,

and Esther Pike's household, including two children in San Francisco.

Like so many monarchical Liberals, Pike could never balance a budget. He overspent routinely and had to plea to the higher-ups for extra funding—making the new figure the budget-ceiling for the next fiscal-year.

I write about monarchical presumptions and overspending in my post from 17 June, about Orlando di Lasso and the Duke and Duchess of Bavaria. The royal couple spent a fortune on music and art and bankrupt their kingdom. James Pike likewise fell victim to this monarchical presumption, that he could spend as much money as he liked:

Page 65-6: By his last year at Christ Church (Poughkeepsie, New York) he was accumulating

significant administrative problems and personal opponents. . . . The plain fact was that Pike had

badly overspent his church budget in enacting his new plans and programs.

Page 71: Joseph Blau, professor of philosophy (Columbia University) complained about the

"expansionist, imperial policy."

Robertson quotes from a published obituary after Pike's death from a man who knew him, that Pike "gained a reputation for glibness and raw publicity-seeking."

Pike the Populist, a Man of the People, a huckster, a man with monarchical aspirations, will always frighten a significant number of us. Others just accept his generosity and dynamism at face-value and turn a blind-eye to the moral compromises he makes.