The Manchurian Candidate, part I

The Manchurian Candidate Revisited

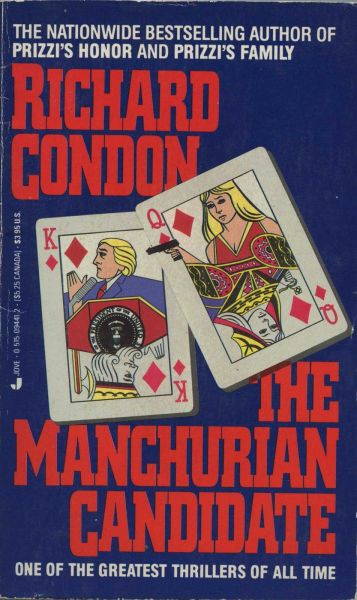

The Manchurian Candidate, published by Richard Condon in 1959, had a lot going for it. For one thing, it tells a very topical story for 1959, a conspiracy by Soviet and Chinese intelligence officers to steal the U.S. Presidential Election of 1960 and substitute their own safe-candidate to become the next President.

They hatch the plot in 1951, capture an American soldier during the Korean War, brainwash him to work as an assassin for them, and let him re-enter American society as a civilian. They let him take his time to mesh gears with civilian life, and minimize contact with him over the next few years, in order to avoid exposing him.

For such an outlandish story, Condon tells it convincingly, even borrowing authority from ruthless Soviet leaders like Joseph Stalin who died in 1953, and Lavrenti Beria, who died at the end of that same year—denounced by Nikita Khrushchev and executed.

Soviet-sympathizers in America loathed The Manchurian Candidate. They knew that Condon had created the perfect anti-communist propaganda piece. Candidate defines America and Americans through a harsh, urban, quasi-ethnic idiom, that mostly works, even if it impresses non-urban, non-ethnic readers as foreign. The snappy dialogue may remind readers of Billy Wilder movies.

For the Soviet and Chinese leaders, the Korean War occured at the right time. They could study the troops of the American military forces, decide which soldier best suited their needs, and drag him off the battlefield to their testing-center across the border in Manchuria. The Chinese psychiatrist, Yen Lo, who leads the testing center, brags that he does not merely brainwash American soldiers. He has him dry-cleaned.

A dictator enjoys many advantages over a democracy. He does not have to stand for election, so he does not need congressional or judicial approval. He has no obligation to inform the public about his actions; and the toadies whom he employs work directly to him, so no one else needs to know what he is doing.

The dictator has to minimize the number of people who know about the plot, and for ten long years, it remains a closely-held secret. But a problem arises when a few soldiers in the assassin's unit get wind of the basic plan through recurring nightmares. They have to experience again and again the assassin murdering two of his own men. Although exhausted from a lack of sleep, they also study the Soviet- and Chinese officials in their nightmares, and make notes about their appearance, the uniforms they wear, and the ranks they hold.

The joint Soviet-Chinese plot involves, it turns out, assassinating the Presidential nominee during his acceptance speech. The assassin's former commanding officer arrives to confront him—still not knowing what the conspriracy wants the assassin to do. The commanding officer has to de-program him, if he can, before that happens.

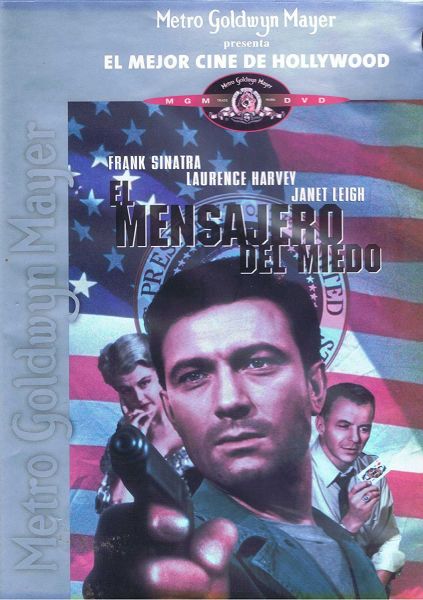

With John Frankenheimer directing a first-rate cast, Candidate became a movie in 1962. It arrived just in time for the real-life assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, which caused both the novel and the movie to hit the skids. United Artists withdrew the movie out of embarrassment and guilt. No one saw it again until U.A. released it in 1988.

The parallels troubled a lot of people. Both the assassin in the novel and Kennedy's real-life assassin Lee Harvey Osward are military marksmen. In both cases, a Soviet conspiracy lies behind the plot. Congressional sub-committees and the Warren Commission concluded there was no conspiracy in the assassination of Kennedy—just a crazed, lone gunman; but no one believed it. Jack Ruby shot Oswald to silence him before he could talk. We can only guess what Oswald would have revealed about the assassination, if he had had the chance.