The Masks We Wear

The Masks We Wear

Over the years, I have watched The Mask, starring Jim Carrey, a dozen times, since it appeared in cinemas in 1994. In the beginning, I just laughed myself sick watching Carrey interact with his dog Milo. The scenes of him going through changes in personality and intention, when he put the mask on, fascinated me. He had to try to persuade a psychiatrist that the transformation was real, but the psychiatrist was buying it.

No matter how zany Carrey's character is, his crush on and longing for Cameron Diaz will resonate in the hearts of guys in the same situation. We also sympathize with his longing to be more than a miserable bank-clerk. We share his hatred of his querelous landlady, his overbearing boss, and the dishonest auto-mechanics.

So I was surprised to find the movie-critics at Rotten Tomatoes and Imdb had just a luke-warm reaction to The Mask. At least they liked it, but the movie deeply divided the viewing public. Even the people who liked it did not care much for Carrey's corny romance with Diaz. The viewers who hated the movie expressed dislike for Jim Carrey's "insanity" and the computerized graphics. Who Framed Roger Rabbit came out in 1988, Cool World, starring Kim Basinger, came out in 1992; so everyone knew about CGI technology, and they disliked copy-cats, and that was before CGI started playing such a big part in practically every movie that has come out since.

Most viewers who liked The Mask mentioned Carrey's hilarious antics, his good-natured practical jokes, and his dog Milo. But as I watched the film for the sixth time, I realized we were all missing the movie's most important insight. Ben Stein, who plays Carrey's psychiatrist, advertises his book, titled The Masks We Wear, and he discusses it on a talk-show: "We all wear masks, metaphorically speaking," the psychiatrist says. "We suppress the 'Id,' our darkest desires, and adopt a more socially acceptable image."

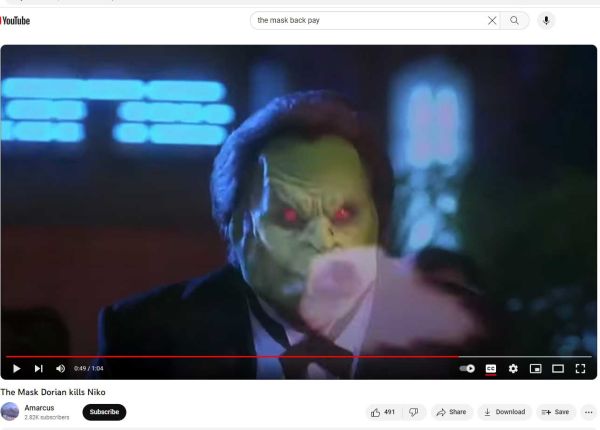

Jim Carrey's "mask," however, does just the opposite. It reveals the "Id" for all to see. Jim Carrey's Id makes the viewer like him more. He wants to sing and dance; he wants to court pretty girls, like Cameron Diaz, and play practical jokes on people he dislikes. Another character, however, puts on the mask and transitions scarily from a minor hoodlum to a super-human monster. The hoodlum's Id-self wants to sneer at his mob-boss, demand his back-pay, then dish out payback! He riddles his boss with bullets that he spits from his monster-mouth.

Most people do not bother with embodying their Id-self personally. They would rather let someone else do that—a sports figure, a political candidate, a media figure, or someone else. The proxy does what we private citizens cannot risk doing ourselves, like sneering at our enemies and dishing out payback. The problem arises when we realize the proxy is not the same as our Id. The proxy may have a will of his own, that we cannot control. Especially in the political realm, letting the proxy operate in our stead can have consequences that we never dreamed possible.