The Nazis and Socialism

Since the biggest and most destructive dictatorships of the 20th century used the word "Socialist" in their names, we need to understand what socialism really means. The Soviet nation identified itself formally as the "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics." The Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin caused the deaths of millions of Russians—ruthlessly crushing any dissent to his pathological leadership. After Stalin's death in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev continued Soviet repression when he crushed the Hungarian Revolt in 1956 and errected the Berlin Wall in 1961.

CCCP are the Russian initials for "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics"

The Soviet one-party state East Germany identified itself by its formal name "German Democratic Republic," led by the political party "Socialist Unity Party." In 1961, the infamous Walter Ulbricht tried to reassure East Germans that he had no intention of cutting off East Germany from the West. In fact, he supervised the building of the Berlin Wall, which did exactly that! But the order to do so had come down from Khrushchev in Moscow. Ulbricht behaved like the typical unctuous toadie of his Soviet overlords; on the other, and devious manipulator of his own people. He employed every trick to allow himself to stay in power, all in the name of socialism.

The German acronym Nazi, on the other hand, stood for the "National Socialist German Workers' Party." Traditionally, political scientists have identified the Soviet Union as politically extreme-left; Nazi Germany as politically far-right. So why does each group identify itself as Socialist? In order to deceive their subjects? I say not. Socialism defines both nations to a T.

Socialism can fit a number of different political situations. One aspect of it however must remain constant: social ownership of property and social hegemony over private spaces, private wealth, and individual freedom. Karl Marx defined socialism best when he talked about family-life and child-rearing. He wanted to replace "home" education with "social" education. Socialism starts with the socialization of people by their government. Put everyone through the same training and education, so that they will all think the same. No one will think of himself as better than anyone else, since the training will beat those kinds of thoughts out of him.

The Nazis also believed in a social upbringing and education. They took children from their homes early in life and socialized them with Nazi values. The children's parents hardly ever saw them. The Nazis had a name for the procedures to further the National Socialist culture: Gleichschaltung. Gleichschaltung consists of two words that aptly describe the socialist society. Gleich, means "the same." Everyone gets the same treatment—the Nazi take on equality. Schalten means to connect something. Gleichschaltung, therefore, means to connect every aspect and function of the society to the same control-panel, ein Schaltbrett. Nothing happens in the society that the government doesn't spin and control. Every organization was headed by a Nazi.

I am not pursuing a relentless, pedantic logic to make this point. The Nazis make the points for me. They instituted Gleichschaltung and thoroughly controlled Germany for the duration of the regime. Many Germans would like to go back to it, just as many East Germans would like to go back to the Soviet model. They liked the equality and the "coordination" of the society.

National Socialism

The Public Broadcasting three-part series "The Rise of Nazism" ran first in the fall of 2019 and runs again this week on most PBS stations. Like accidents involving jets or cruise ships, a lot of factors worked on the Nazi accident. You could even call Hitler the Accidental Dictator. That should quell Liberal angst over the inclusion of "socialist" in the Nazi party name; and Conservatives angst that Hitler was a Germanic Donald Trump. After all, the Nazis did not name their party the "National Capitalist Party."

Most people do not remember a lot about the Nazis. They governed Germany many years ago, and everyone from that generation has passed on. They governed ruthlessly and ruinously, and made their ascent to power with a great deal of prevarication. They wore various masks in order to appeal to a wider range of people to assure their victory in the elections; but the Nazis are not accidental Socialists.

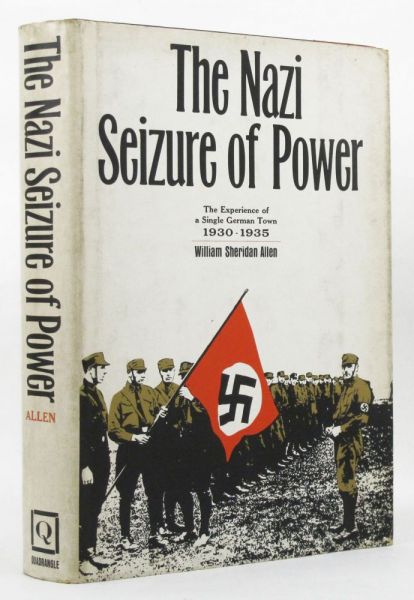

I base that opinion on a book by William Sheridan Allen, The Nazi Seizure of Power, published in 1965, and revamped for a new edition published in 1984. Professor Allen taught history at the State University of New York at Buffalo and basically researched the rise of the Nazi Party in a medium-sized town in Germany. He defined the Nazi culture by following countless paper-trails of the Nazi leaders—the text of their speeches, leadership conferences, and their personal correspondence, and he conducted interviews with Party memberss to find out what instructions their leaders gave them. Allen wanted to know everyone who played a part in the functioning of the Nazi society. It makes his history extremely valuable.

As far as how the Nazis defined themselves, Professor Allen sets everyone straight quickly:

Page 31: In the early months of 1930, the NSDAP held a meeting nearly every week, advertised with such titles as "The German Worker as an Interest-slave of Big International Capitalists," or "Saving the Middle Class in the National Socialist State."

A housewife put it clearly: "The ranks of the NSDAP were filled with young people. The people who joined did so because they were for social justice, or opposed to unemployment."

The fact that Nazi rhetoric appealed to voters with buzzwords still in use by the Left today—nearly unchanged after eighty years—gives me the creeps. Just like in contemporary America, the slogans appeal mostly to young leftists.

Professor Allen continues:

Page 134: Three days later, a Nazi member of the Prussian Parliament spoke on "Down with the Dictatorship of the Money-Bags."

The anti-capitalist rhetoric had one principal target, the Jews. Jewish-owned businesses featured prominently in every German city, much of it financed with Jewish start-up capital. The Nazis took their revenge by confiscating Jewish businesses and staffing them with Nazis. The Nazis also stole Jewish art and jewelry; they confiscated the Jews' expensive homes, and eventually deported them. Like leftists today, the Nazis hated the Jews for their sense of "privilege" and the power they held over German workers—and now look at them, deballed and dispossessed!

Professor Allen touches on one other impressive feature of Nazi moralism—smoking! In the 1930s, everyone smoked—Germans, Americans, Frenchmen—they all smoked. Hitler himself forbade it in his presence. The Nazi upstarts touched off an anti-smoking campaign:

Page 171: Twenty-five years later, Karl Querfurt still retained vivid memories of one incident. As soon as he sat down at his assigned place (for a city council meeting) Querfurt took out a big cigar

and lit it. Immediately an SA (stormtrooper) man came over to the SPD (German Socialist Party) table and said, "Put that out! You can't smoke here!"

Querfurt exhaled slowly and surveyed the Stormtrooper. Then he leaned forward and said, "Now listen closely. Are you SA people running the City Council or are we city councillors? I'll smoke

here if I like." The SA man turned on his heels and walked away.

It is often difficult for political scientists to read the day-to-day motives of voters, how they respond to the pace of change, their vindictive feelings about ideological opponents, or making the problems of the moment go away. The voters may not feel that the policies of the ruling parties will insure the safety of the public. They might choose more extreme candidates to make them feel safe.

Thus, Allen writes about the election of 1932:

Page 106: One final item emerged from the voting totals for the elections held in March and April,

1932. The Communist Party went into the elections with 115 votes, rose to 182, and then dropped

again to 117. From this it seems clear that at least sixty-five Northeimers switched from the

Communists to the Nazis.

Subsequent elections were to show increasing numbers switching back and forth between the two

totalitarian parties. Obviously some Northeimers were ready, by 1932, for any dictatorship, as

long as it guaranteed revolution.

Modern left-wing pundits may act shocked that anyone would draw parallels between the Soviets and the Nazis, but the voters sure did!

Furthermore, Allen writes that those voters had lost confidence in the leadership of the mainstream parties:

Page 86: Most who joined (the Nazis) did so because they wanted a hard, sharp, clear leadership.

They were disgusted with the internal political strife of parliamentary party politics."

The divisions between the leading political parties has gone on for so long, we no longer pay them any attention, but deep down, we hate them for destabilizing our great country, and we look for the opportunity to "throw the bums out."

Other interviewees told Allen that they had wearied of the partisanship of the mainstream political parties. The parallel to Germany's pre-Nazi situation resembles so much the situation of America's contemporary political smear campaigns, it sent shivers through me,

Page 90: But its chief effect (of the smear attacks) was to debase the nature of politics and to destroy the foundation of trust and mutual respect without which democracy cannot succeed.

When politics becomes a matter of vilification and innuendo, then eventually people feel repugnance for the whole process, (and) yearning for a strong man who will rise above the petty

and partisan groups.

But Allen does not trust in a "strong man," and he has no particular trust in a government-centered "socialized" society. He quotes the British political scientist William Godwin who wrote, "The true supporters of government are the weak and uninformed, and not the wise."

Americans need to pay attention to the Nazi socialization process, the eradication of private spaces, and the inclusion of Nazi Party members in all the functions of the society. Therein lies the truth of socialism, that hooks us all into a government-centered life. I doubt a well-to-do leftist really wants to face the consequences of socialization, but the lure of "coordination" by a strong man remains a threat to any "disorganized" free society. (Professor Allen uses "coordinate" in this context nineteen times between page 223 and 232.)

Note how Allen describes the "destruction of society" as the loss of private spaces. In the case of Germany, private spaces took the form of clubs for the average citizen. The Nazi Party henchmen warned the clubs, "They must abandon their exclusive nature." They also told the clubs to abstain from "senseless competition."

Page 298: What social cohesion there was in the town existed in the club life, and this was

destroyed in the early months of Nazi rule. With their social organizations gone and with terror

a reality, Northeimers were largely isolated from one another.

This impressed me very much—that "social cohesion" depends so much on "club life." Professor Allen makes one other point that bears on the American experience The "coordination" of Germany went more smoothly, thanks to the many government employees. Since our nation has a significant population of government workers, this should concern us.

Allen writes about the government workers:

Page 298: The process was easier in Northeim than in other places, since the town contained so

many government employees. Because of their dependence on the government, the civil servants

were in an exposed position and had no choice but to work with the Nazis, if they valued their

livelihood. . . . Northeim's teachers—who formed the social and cultural elite of the town—

found themselves drawn into support of the NSDAP almost immediately.

The local Nazi "strong man" in Northeim was a man named Ernst Girmann. Professor Allen read through page after page of Girmann's memoranda, official minutes, letters, and personal quotes in order to understand the personality of the man—why Girmann became a Nazi and what motivated him to do his job. In so doing, Allen touched on the final important parallel between Nazi Germany and America's contemporary problems—hatred of the elites!

Page 300: Finally, it is possible to construe the actions of Ernst Girmann . . . as expressive of class

divisions. . . . (M)any of the actions taken by Girmann and his closest friends suggest they were a

product of social resentment. Girmann was of the lower middle class and this undoubtedly made

its mark upon him in a town where government and society were dominated by an elite that freely

expressed its cool authority. (italics mine)

Allen continues this thought on the next page:

Page 301: As a result, Girmann did things to the town's elite that he never did to his political

opponents. The same approach characterized all of his relations with the town's upper crust. . . .

Ernst Girmann was possibly attempting to triumph over the environment in which he had grown

up and which condemned him to the condescension of his social betters. (italics mine)