The President as Monarch

"This is now a monarchy? The king is the state? This cannot be."

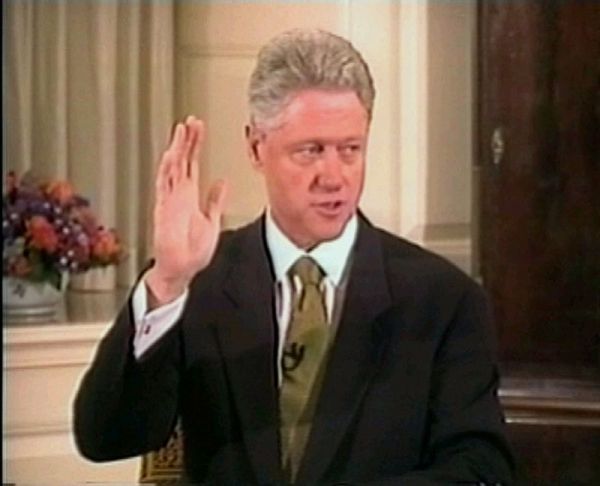

Kenneth Starr, Independent Counsel investigating President Clinton

On 19 July, I posted an article about Becket, a play by French dramatist Jean Anouilh. It concerns a British King Henry II and his boon-companion Thomas of Becket, who later becomes Archbishop of Canterbury. Henry was a typical despotic monarch with a yen for teenaged girls. Becket was his bosom buddy and went along with the monarch's shenanigans; but once Henry nominated him for Archbishop, he changed his tune and warned Henry that he no longer answered to the King but only to the Church. Becket became Henry's arch-enemy!

On 26 July, I posted another article that turned the tables on the Church. I wrote about the Episcopal bishop James Pike, who behaved more like a monarch than a churchman and had numerous women. His secretary Maren Bergrud was his live-in lover. She hated Pike for cheating on her so often, and she wasn't even his wife! His wife lived elsewhere with the couple's children.

That the monarch considers himself above the law just goes with the job-description, so to speak—he is the law! Often he expresses that privilege sexually; but a society only advances if it maintains the law as something impersonal, fixed, and authoritative—in a constitution, for instance. Even with a constitution, we can only control that sense of privilege, not eradicate it, since the public can both enable or disable the power of the constitution.

The conflict reveals an inherent frailty in human psychology, the yen for monarchical rule, to allow our guy to remain above the law. In a society with educated people, we already know the answer, even if we want our man to get away with stuff.

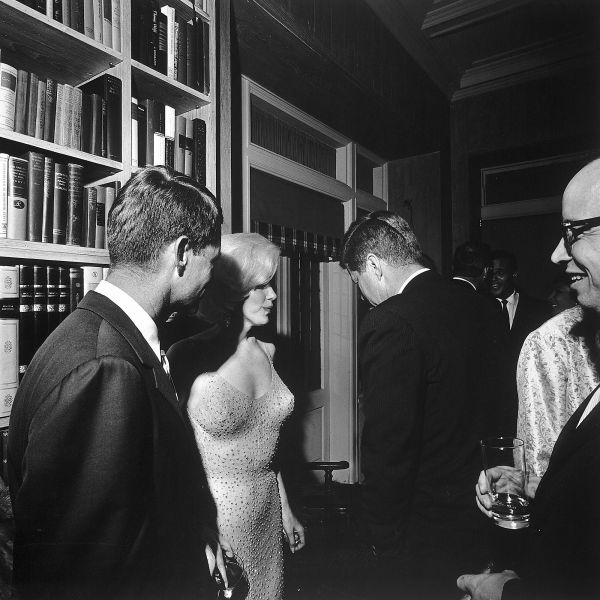

A Harvard professor Arthur Schlesinger published a book in 1973 about former President Richard Nixon, titled The Imperial Presidency; but surely President Kennedy, Schlesinger's personal friend, was as much a monarch as Nixon was. That whole Kennedy "Camelot" thing?

No thanks to Schlesinger, Americans know now that Kennedy brought lovers in the White House, numerous lovers. Kennedy employed a "special assistant," Dave Powers, to procure them—even a nineteen-year-old White House intern.

President John F. Kennedy, left, Marilyn Monroe middle, Robert F. Kennedy to her right, and Arthur Schlesinger to his right

Evidently, Schlesinger also knew about the lovers and never mentioned them in his writings about Kennedy. A contemporary described Schlesinger as a "Kennedy courtier," a sort of high-end royal servant. Richard Nixon was ironically too bourgeois for Schlesinger's taste.

Kennedy's Successor

William Jefferson Clinton became President of the United States in 1993, replacing the lackluster George Bush, Sr., who admitted foolishly, albeit truthfully, that he had trouble comprehending "the vision thing." President Clinton comprehended that, as the nation's chief executive officer, he had an agenda mandated to him by his voters, the Democratic Party, and from legislators in Congress, regarding education, free trade, tax reform, and reviving the spirits of the nation.

Like President Clinton, I am left-handed. One day, during his administration, I checked into a hotel to spend the night. The hotel clerk stopped what he was doing and watched me sign my name in the guest-book. He asked, "What do you reckon it is about left-handers?" I couldn't tell if he admired lefthandedness or suspected it.

Clinton had an aura of purposefulness and leadership that made him a stand-out figure of his time. He courted Republican congressional leaders, harried them with proposals and compromises, and worked tirelessly to push through legislation. Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole referred to his tax legislation as a "Taxosaurus," but Clinton pushed it through Congress.

Tall, dynamic, and viscerally handsome, he radiated an aura, carried himself well, and bristled with strength. He recruited an absolutely loyal cadre of staff people who admired him for his activist spirit, even as he drove them imperiously. By the time his first term ended, he was a shoo-in for a second term.

Bob Dole and Jack Kemp ran a perfunctory campaign for the Republicans. An observer said Dole's manner at a campaign stop reminded him of "a Catholic wake for a departed friend." Clinton and his Vice President Al Gore won re-election in a near landslide in 1997. Just a year later, he nearly lost it all when allegations about his behavior as Arkansas governor arose. The allegations dogged him for the rest of his second term.

Surely, it is one of the unsung strengths of our nation's legal system that a re-elected President can return to power with momentum to spare, then have to stop on a dime, if sufficient cause is found. He may face indictment, impeachment, or just a lawsuit. The principle is that no one is above the law. It is that simple. The strength is in the will of the nation to uphold the law above social rank, wealth, or political power.

The Legal Facts About Clinton and Lewinsky

I can still remember the landslide victory of Richard Nixon in 1972. After great fanfare, the nation ushered him into office with all the dignity and grandeur due to such an occasion. Little did anyone know that two journalists at the Washington Post were already working on unverified rumors of a dirty-tricks campaign carried out by Republican operatives, that Nixon knew about and sanctioned. In the movie All the President's Men, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, the journalists continue working while a TV plays in the background, showing the re-elected President relishing the joyous applause of his supporters. Congress got wind of the rumors and convened the Office of the Independent Counsel to investigate. In the summer of 1974, the nation's commander-in-chief resigned from office, disgraced.

Fast-foward to January, 1998. A new generation of attorneys working for the Independent Counsel investigated President Clinton's legal problems that dated from his years as Governor of Arkansas, such as the Whitewater land venture and the Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan. When the phone rang, attorney Jackie Bennett took the call. An anonymous voice at the other end said things that put Clinton in line to follow Nixon. Bennett listened, then summed up the conversation:

"So let me get this right," he said slowly. "You've tape-recorded calls

from a woman who had a affair with the president. She's lied about it

in the Paula Jones case and is trying to get you to lie about it. People

are helping her get a job to buy her silence. . . ."

Jones was a low-level Arkansas government employee who had filed a sexual harrassment lawsuit against President Clinton. Jones's attorneys had heard rumors of Clinton's other girlfriends, and one of the girlfriends told the caller that she had lied about her own affair with him during a deposition by Jones's attorneys. That set a lot of things in motion. To the attorneys of the Independent Counsel, it sounded a lot like perjury and witness-tampering. Those charges would get the ordinary citizen a prison sentence.

Another call followed from the same anonymous caller, who tried to increase her anonymity:

"Let's say," she began, "that I've got this friend who is a potential

witness in a civil suit involving the president, and she knows about

the president having an affair with a woman, and they're trying to

get my friend to lie about it."

I remember a hilarious episode of the 1960s sit-com I Love Lucy, where Lucy visits a psychiatrist to talk about her "friend's" personal problems. The kindly psychiatrist went along with her charade, dropping helpful suggestions that Lucy could pass on to her "friend."

The anonymous caller, encouraged by the attorney's replies, dropped a veil: "You guys know me." Susan Schmidt and Michael Weisskopf, writing in Truth at any Cost, published in 2000, relate the following on the anonymous caller:

Her name was Linda Tripp. She had been a secretary in the White

House counsel's office when Vincent Foster died. . . . She claimed

to have relevant information, and now someone was leaning on her

to commit perjury.

Tripp identified that "someone" as Monica Lewinsky. Schmidt and Weisskopf continue:

The next part of Tripp's narrative got the full attention of her guests.

Clinton, Lewinsky told Tripp, had advised a strategy of "Deny, deny,

deny." . . .

Tripp had been subpoenaed by the Jones lawyers to answer questions

about a woman named Kathleen Willey, a White House volunteer. . . .

But Lewinsky worried that the Jones lawyers would ask Tripp about

other women, including her. She had urged Tripp to lie for her own

protection. If she didn't, Lewinsky warned, Tripp might lose her job . . .

and if Tripp's story didn't jibe with what Lewinsky and Clinton were

saying under oath, Tripp might be accused of perjury.

Tripp told the attorneys she was pretty scared. They tried to calm her down, but her information had shaken them, as well.

If Tripp was telling the truth . . . the implications were staggering,

both for prosecutors and the president. He realized the public would

probably not distinguish the sexual aspects of the case from the

criminal.

Attorney Stephen Binhak listened to Tripp's tapes and summed it up for the other attorneys:

"Listen to this. . . . We're up to four counts of obstruction of justice,

maybe conspiracy." . . . Tripp was a witness once-removed; Lewinsky

was a participant with a direct tie to the White House. Not only had

the President told her to deny everything, she told Tripp, he planned

to do the same under oath. . . .

(Lewinsky) left no doubt how closely (Vernon) Jordan's job-hunting

help was tied to her silence. . . .

Before signing the affidavit, she wanted a job offer. . . . "I'm not

signing it until I have something."

The attorneys concluded, "Paula Jones had the right to have the merits of her claim weighed by a judge or jury, not by the man she accused in her lawsuit. 'The lowliest person in the country can sue the most exalted and get a fair day in court,' said Binhak."

The Independent Counsel, himself, Ken Starr, informed his staff that President Clinton intended to oppose the investigation of his actions by invoking executive privilege. Starr "consulted with Sam Dash, the old Watergate hand, who agreed that if Clinton invoked executive privilege, he would be abusing the Constituion to save his own skin."

Starr posed the question rhetorically to the other attorneys in the Independent Counsel's office, that I pose repeatedly in this essay, "This is now a monarchy? The king is the state? This cannot be." It is the point I make about men with monarchical tendencies taking advantage of women who are in a subordinate position to them.

But Starr did not understand that he and Clinton, both residents of Arkansas, were proxies in a much larger battle, waged by the opposing sides of the American political culture. Their mutual antipathy dwarfed the practical issues of the case. The Clinton case defines the watershed better than anything Bishop Pike. For one thing, it was a lot nastier.

Ronald Brownstein, the typical Clinton courtier, stood behind the President. He writes in his book The Second Civil War, "(T)he scandal that surrounded Clinton's affair with Monica Lewinsky was not a contributor to, but an outgrowth of, the polarized atmosphere." Brownstein just ignores the legal issues Clinton faced. The behavior of Starr, the actions of Tripp, and the litigation lodged by Paula Jones—"All of these swirling circles testified to the depth of conservative antipathy toward Clinton."

Brownstein writes about other Democrats angry at Starr. Joan Blades and Wes Boyd, for example, started MoveOn.org to protest the attention paid to President Clinton's sex life, which they saw as politically motivated. Likewise, Markos Moulitas started the Daily Kos for much the same reason. Both groups focused almost entirely on the sexual testimony and imputed a squeamish moralism as a motive to Starr and the OIC attorneys.

Television comedy made light of the situation, such as John Goodman's hilarious impersonation of Linda Tripp on Saturday Night Live and James Carville's scandalous comment about Paula Jones's "trailer-park" mentality. Hell, it takes one to know one. Carville's behavior personifies that trailor-park mentality better than Jones's. It reminds me again of Henry II's disdainful attitude toward the peasants in his own kingdom.

Carville and Goodman's behavior did not help the "polarized atmosphere" either, did it? Each side blames the other, and the accusations get shriller. We've heard it all before. Why not do something pro-active, for a change, and divide the country?

It should concern Republican voters and Republican politicians, even if the experience seems like business-as-usual for the Democrats. If we want a nation with a prevailing rule of law to govern the behavior of its citizens, then everyone has has to have his day in court—from the lowly Paula Jones to the President of the United States.

Curiously, James MacGregor Burns asks in his book The Democrats Must Lead, "What does it take to lead? . . . Above all, moral purpose and conviction." If the Democrats had their own country, they would not need to defend a leader who has let them down, or worry about the Republicans trying to undermine their leadership—making them hostages to political disunity.