The Real Cost of Treason

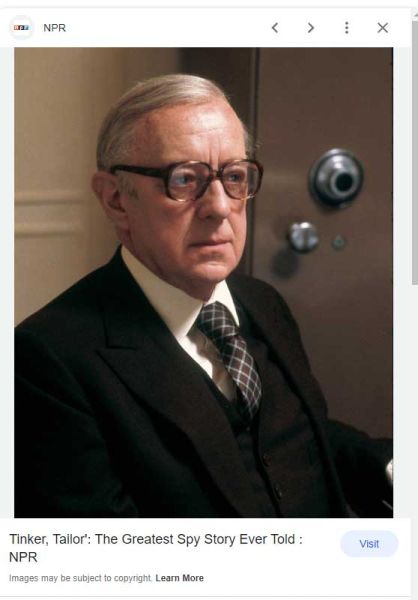

Like a lot of Americans, I discovered John leCarré in 1980 when Public Television ran the BBC mini-series of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. I thought it was so good, I decided to read everything that leCarré wrote, starting with Tinker, Tailor, since the mini-series had given me a head-start on it, and I knew how it would end.

After I had read it several times, I tried to explain the plot to a friend and realized the novel lacks a clear starting-point. How do you explain the plot, if it begins a year or two before the novel does?

Several of the characters in Tinker, Tailor could say the novel begins from their vantage points, and leCarré gives them the credence, substance, and depth to prove it.

Viewers walked out of the 2011 filmed version of Tinker, Tailor, complaining they could not follow it. The complexity of Tinker, Tailor reminds me of a line from E. M. Forster's Howard's End:

Margaret realized that the chaotic nature of our daily life differs from the orderly sequence that has been fabricated by historians. Actual life is full of false clues and sign-posts that lead nowhere.

I think I can sum up Tinker, Tailor in just one line. It concerns the collateral damage of one man's disloyalty to his country. Leftists of our country wants to justify the disloyalty of Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden as an act of conscience. I say give the leftists their own country, and see how they feel when Manning or Snowden betrays their secrets, or airs their dirty laundry. Let them feel the demoralization the rest of us feel.

The novel concerns the revelation that a double-agent in the British Secret Service has betrayed the nation's secrets. LeCarré's spy-catcher George Smiley goes to work to expose him. Just the task of tracking down the spy unnerves Smiley. He even has the humiliation that the double-agent has had an affair with his wife. Faced with his burdens, Smiley pauses:

He stared at his chubby hands, watching them tremble. Too old? Impotent? Afraid of the chase?

Or afraid of what he might unearth at the end of it?"

As Smiley interviews the double-agent's other victims, his suspicion hardens. He harbors anger for the double-agent, but keeps it in check and proceeds with the courage of a solitary. LeCarré dwells on Smiley's tortuous thoughts, his patriotism, and his cynicism about his ambitious superiors who worry about.

He interviews Connie Sachs, the Service's "queen of research" who has known for some time of a double-agent. She never could persuade her superiors to let her track him down. When Smiley asks her to tell him about Aleks Polyakov, the double-agent's controller, she is reluctant: "Oh, George! Why do you have to drag up Aleks?" It opens an old wound, and she starts weeping. Like Smiley himself, Connie knows who the double-agent is, a man she trusted and loved for years since World War II.

As Smiley leaves, Connie tells him, "If it's bad, George, don't come back. I want to remember you as you were. My lovely, lovely boys."

Smiley has to broach the subject of the double-agent with his wife Ann, who proposes to "divorce him from the family, from our lives, from everything, here and now. I throw him into the sea. Do you understand?"

Smiley also has to interview a fellow-officer of the secret-service. Smiley realizes the double-agent has been the fellow-officer's homosexual lover. He has known for some time that the double-agent goes "both ways"—in his personal life, as well as in his professional life! Smiley runs into the same problem he has in his other interviews. The fellow-agent can barely tolerate the idea that he has to talk about their relationship. During the interview, he drink a whole fifth of vodka.

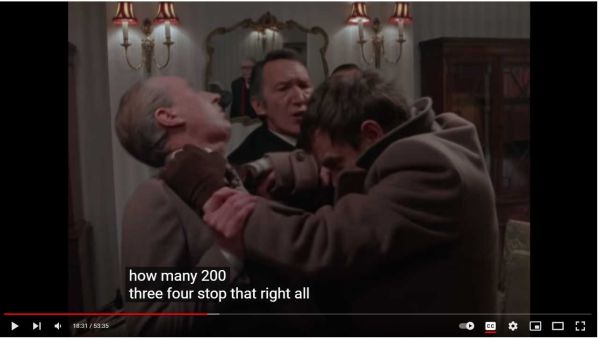

Smiley finally tracks down and exposes the double-agent. A fellow-agent helps to take the double-agent into custody; but the double-agent's disloyalty affects the fellow-agent personally. He grabs the double-agent by the throat. Other officers have to restrain him. Like all the others, he hates the double-agent for betraying the loyal, dedicated men and women of the Service.

In custody, Smiley watches the double-agent shrink in moral dimension. He falls back senselessly on left-wing clichés. Their pertinence in contemporary left-wing circles should concern thoughtful people, Left or Right:

"We live in an age where only fundamental issues matter. . . .

"The United States is no longer capable of undertaking its own revolution. . . .

"In capitalist America economic repression of the masses is institutionalized to a point that not

even Lenin could have roreseen. . . ."

Smiley passes all this through his critical brain again and "shrugged it all aside, distrustful as ever of the standard shapes of human motives;" and I could be wrong, but Smiley infers that the double-agent goes forward with discredited talking-points, that he has not reviewed or edited in some time.

"Treason is very much a matter of habit, Smiley decided."