The Reality of National Bigness

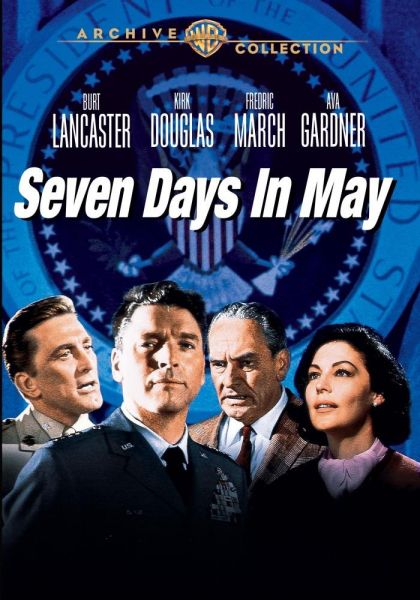

The authors Fletcher Knebel and Charles Bailey collaborated on a novel titled Seven Days in May that they published in 1962--during the Cold War, at a time when tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was high. Seven Days in May made quite a stir and appeared as a movie in 1964 starring Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas. The film-script written by The Twilight Zone's own Rod Serling, moves the novel to the political Left, focusing criticism on the military. Most of the cast--March, Lancaster, and Douglas--typically voted Left.

The novel concerns the worry of the military, during the Cold War, that the Soviet Union would cheat on its obligations to the UN for transparency, regarding its nuclear weaponry. The military chiefs do not believe that the U.S. President, a man named Jordan Lyman, has the backbone to force the Soviet Union to comply with the UN restrictions; so the chiefs decide to force the issue, lauch a coup and remove President Lyman. Lyman gets wind of the plot and takes action to head off the coup.

During the Cold War, opinion regarding the Soviet Union took a negative turn, especially in light of the court cases regarding the U.S.'s nuclear bomb technology. Most of America supported a strong defense and containment of Soviet aggression, but a vocal minority on the Left supported Rapprochement, a policy that took the official name Détente, from the French word meaning "disarmament". The Nixon administrartion adopted Détente as official policy seven years later.

In Seven Days in May, President Lyman can hardly believe the military chiefs would attempt to seize power and threatens to court-martial the whistle-blower. The President asks a trusted advisor for his opinion: "But you don't really think that the military would try to seize the government just because they are underpaid, do you?"

The congressman replies, "Of course not. But it's part of the climate. Jordie, this country is in a foul mood. It's not just the treaty (with the Soviets), or the missile strikes (labor action). . . . It's the awful frustration that just keeps building up and up. . . ."

"But a Pentagon plot?" Lyman asked.

"I'm talking about the climate, Jordie. The move could come from anywhere."

So, the current disunity and division are nothing new in this country, and the fact that "the move could come from anywhere," during a crisis, must worry a lot of people. It makes you wonder who your real friends are.

No one knows that better than President Lyman. In Seven Days in May, he looks through countless files to see which members of his cabinet he can trust with the knowledge of a conspiracy by the nation's military leaders:

page 84: Mentally, (the President) began to thumb through his administration, ticking off men he'd appointed in the sixteen months since his inauguration.

Page 85: He hadn't gone far before he realized . . . he was discarding name after name of men he had picked to do important jobs, but who couldn't be counted on for this one:

- personal secretary Girard, yes;

- Senator Ray Clark, yes;

- the Secretary of State, no;

- the press secretary, no;

- the special counsel, no;

- the Secret Service Chief, yes.

After that, the President "ran through the deputy secretaries and assistant secretaries, the numbers of commissions, even the courts. . . . He really didn't know any of these men well."

Seven Days in May should give the reader something to think about, namely that the vast bureaucracy of the U.S. government isolates the President of the United States. He has to deal with difficult issues that require extreme discretion that limits the number of advisors in the loop. He has to risk antagonizing his closest associates when he keeps them at arm's length. He has to trust in very few people, and in the contemporary context, the insights could not be more topical.

An Uneasy World and Conflicting Voices

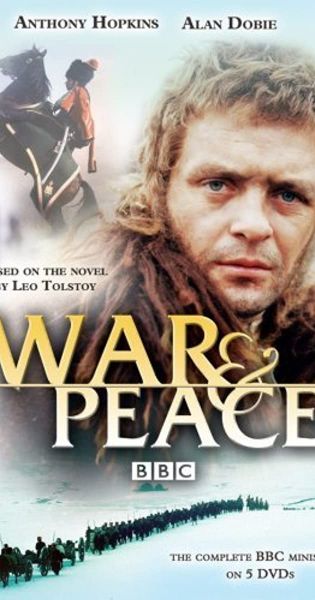

Leo Tolstoy also weighs in with a realistic presentation of government in its highest ranks, in his novel War and Peace. In early 19th century Russia, a monarchy headed by a "Tsar" or "Czar" ruled the Russian Empire. Tolstoy describes this situation with the confident hand of an insider. The text in War and Peace reads like a limited-circulation memorandum:

"The above-mentioned were the most prominent personages about the Tsar, and among them, the foreigners were in the ascendant." Tolstoy's reference to the Tsar and his "foreign personages" is interesting, since the Tsar himself was more German than Russian. Tolstoy continues, "In this vast, brilliant, haughty, and uneasy world, among all these conflicting voices, Prince Andrey (Bolkonsky) detected the following sharply opposed parties and differences of opinion."

The text reads a lot like America's own volatile situation, Russia felt threatened by Napoleon Bonaparte and the French army, and needed to mobilize its own army to defend the nation. Like America, the leaders had a variety of opinions about how to proceed. Sometimes the leaders had sharply opposing opinions about each other.

"The first party consisted of Pfuel (a German General) and his adherents—military theorists who believed in a science of war with immutable laws. . . .

"The second party was directly opposed to it. . . . They were Russians. . . .

"The third party, with whom the Emperor expressed the most confidence belonged to courtiers who . . . spoke and reasoned as men usually do who have no convictions but wish to pass as if they do have them. . . .

"The eighth and largest group . . . desire neither peace nor war, neither an advance or a defensive camp . . . but only as much advantage and pleasure for themselves. . . ."

Think of that! At least eight groups of people bunched around the highest levels of the government, all of them clamoring to make their opinions known. Tolstoy writes that Prince Andrey was picking up signs that another group "was being formed and was beginning to raise its voice. This was the party of the elders, reasoned men, experienced and capable in state affairs . . . to consider the means to escape from this muddle, indecision, intricacy, and weakness."

Making the situation much worse is the detachment from the daily affairs of state by the head of the nation, the Tsar Alexander. One senses that the statesmen and military leaders routinely bypass the Tsar and communicate only with each other, leading to the conclusion that this crisis will not end neatly, if it ends at all.

The point I am trying to make is that America not only has disunity working against its forward progress, it also has to recognize the limits of organization and leadership to deal with the problem. The many organizations, coalitions, and unofficial advisers all have solutions and add to the clamor of a leader's normal workday. The limitations of working-knowledge within a leadership-clique also hinder their ability to utilize the many organizations and advisers who can help them. Bigness in a nation does not transition so neatly to the notion of collective strength and resolve.

Americans need to wise up to the political realities of their own modern nation and undertake some overdue adjustments in its administration. There are more wheels within wheels that run our nation than anyone is willing to recognize.