The Role of Resentment

THE ROLE OF RESENTMENT

I have always liked the film The Manchurian Candidate, released in 1962, about the assassination of a U.S. President; but when the actual assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy took place the next year, the producers of The Manchurian Candidate pulled it from cinemas, and I did not get to see it until years later.

Note Frank Sinatra, as Captain Ben Marco, in the front of the first photo, and beside him Lawrence Harvey, as Sergeant Raymond Shaw, seated next to the woman in the hat.

In the second photo, we see Sergeant Shaw seated beside Dr. Yen Lo, played by Khigh Dhiegh.

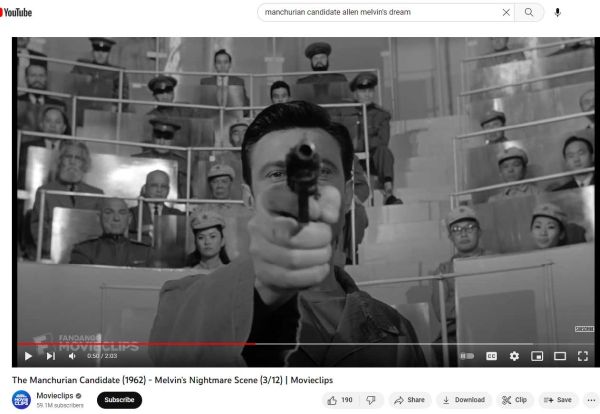

Nothing about the movie intrigued me more than the idea that you could take American soldiers off the battlefield in Korea, transport them to Manchuria, brainwash them, and make them believe that they were actually in a hotel in New Jersey listening to a group of old women talk about gardening. One American soldier sees both scenes—the women talk about gardening in New Jersey, the Soviet and Chinese in the auditorium in Manchuria, talking about brainwashing. Captain Marco sees the two scenes as if superimposed on one another.

When I found out that The Manchurian Candidate story had come from a novel by the same name, I asked around at bookstores—but none of them possessed copies of the novel, nor could they order any, explaining that it was out-of-print. The Kennedy Assassination really sort of stigmatized it, as if people blamed the novel for the assassination.

However, thanks to author Richard Condon's subsequent successes, such as Prizzi's Honor, filmed in 1985, starring Jack Nicholson, The Manchurian Candidate slowly regained visibility, first as an audiobook, published in 1986 on audio-cassette by Listen for Pleasure, and read by the late actor Robert Vaughn; then in book form in 1993, with a fairly disapproving foreward by Louis Menand. Vaughn's brilliant reading spoiled me. A consummate professional, he brings the characters to life, to the extent that I don't "hear" the characters so well when it read the book.

Vaughn also delves into psychological aspects of The Manchurian Candidate that the movie leaves out. Why, for instance, do the Soviets and Red Chinese choose Sergeant Raymond Shaw for brainwashing? The Chinese psychiatrist Dr. Yen Lo explains that Shaw has a timid character and resentful disposition. "Although the paranoiacs made the great leaders," Dr. Yen states, "it is the resenters who make their best instruments, because the resenters . . . make the great assassins.

"(R)esentment is entirely impersonal," Yen explains, "as opposed to hatred, which presupposes a duel between the hater and the hated. The reaction of the resenter is directed against destiny," which I take to mean that the resenter can find little meaning in his own life. It is "irremedially spoiled," as Eric Hoffer expressed it. The lack of orientation leaves him thwarted, without intentionality.

But the resenter's psychological orientation presents even greater problems to the forward-moving, freedom-loving society, as Yen explains: "This weakness of will is compounded by his need to lean on someone else's will." But whose "will?" Anyone in particular? Yen says, "Note how he is always drawn to authority." Just another team-player, with an impersonal ax to grind. Note that Shaw will kill to please his controllers.

A reader does not have to take the "assassin" thing too literally to understand the problem that Shaw presents a freedom-loving society—not so literally as a murderer, I mean. Shaw can be just another team-player, anxious to please and to get in good with the boss, while slaking his thirst for payback, at the same time.