The Significance of Persona

I first saw Persona in college during an Ingmar Bergman film festival. I remember missing the first fifteen minutes, and I might as well have missed the rest of it. So Persona went in one ear and out the other; but I returned to Bergman's films after college, via PBS, the Public Broadcasting Service. PBS ran the series PBS Saturday Night at the Movies during the Winter of 1976, although exactly when I saw Persona again, I do not remember, now.

During college, I studied Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Something puzzled me about the "Prioress's Tale." The Prioress tells a story about evil Jews murdering a devout Christian child. After she finishes her tale, her audience expresses only a muted reaction to her virulent anti-semitism. Chaucer describes their reaction in a way that stands out from the rest of the text, and I wondered, what is Chaucer's real intention toward this tale?

So I asked my professor. He replied, "Ambiguity is. . . ." I forget exactly what he said—something professorial, I suppose: "Ambiguity is the spice of drama," or something like that. Just "Ambiguity is," is enough. Human kind is often ambiguous, depending on who occupies our intimate realm and how the significant-other feels about things and impacts us with it. (Dr. Jim Stewart, at Furman University, for those who remember him.)

Maybe that is the real lesson of Persona--ambiguity of character. We all get good at role-playing, as we get older. Some of us need it more than other people. If we get good enough at role-playing, become actors, or develop a persona, it can cause problems for us--when the difference between who we are and who we pretend to be—the one side pulling against the other—disrupts our personal orientation and direction, and has a negative affect on our willing-or-unwilling partner.

In Persona, for instance, Ingmar Bergman studies two women, an actress going through a nervous breakdown and the nurse assigned to take care of her. The actress has a strong ego and stays silent. The nurse has a weak ego and talks compulsively. Eventually, the weaker starts imitating the stronger, and perhaps visa versa. The critics talk about how the weaker of the two "submerges" her personality in the other. I will only admit that there's some imitation involved in their relationship.

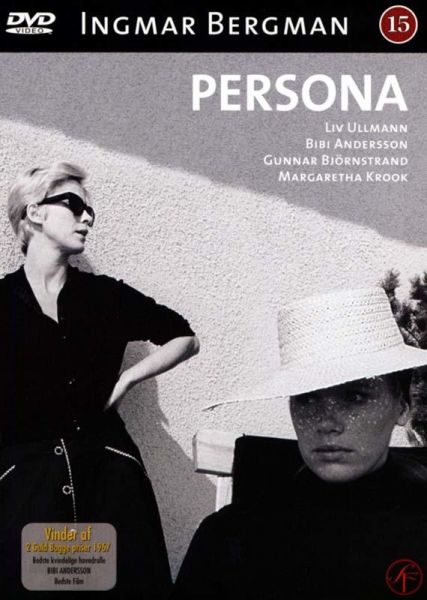

Note how, on the DVD case-cover, Bergman juxtaposes them as twins, or 45 degree mirror images. He uses this visual parallelism in other movies. I also realize, thanks to Bergman, that personalities rub off on each other as a matter of human dynamics. Few film-makers show it as well as Bergman does. He uses this visual, 45-degree parallelism thing in two other films:

I got so hung up on the dialogue, I just switched off the sound and read the sub-titles. I asked myself the question that I asked about another film, The Third Man. Couldn't Persona work just as well as a novel? You could leave out all of Bergman's artsy-fartsy modern motifs. Let the dialogue tell the story. At other times, you might want to turn the sub-titles off, watch the movie, and even enjoy the incomprehensible Swedish dialogue--sometimes one way, sometimes the other. The movie and the script complement each other.

As she prepares herself for bed, the chatty nurse characterizes her life as uneventful but personally satisfying. What she says sums up life for most of us. We want a sense that we are doing the right thing for us, that our path in life has a practiced sort of orientation and reliability:

"I'll marry Karl-Henrick, and we'll have a few children, that I'll raise. All that is decided.

It's inside of me. It's nothing to ponder over. It's a huge feeling of security. Then, I have

a job that I like and am happy with. That's good, too."

Political theory and statistics only tell part of the story of a country. You have to take into account the ambiguity of who we are under our skins and realize that we need a government to give us a sense of direction, to establish the playing field, and the game rules. Otherwise, our lives take place in a vacuum, that leaves us clingy and disoriented.

Persona's sound-track presages industrial-rock. Musical themes in the sound-track reminds me of driving a car with a flat tire, hearing cars honk, some squealing brakes, and some near-misses. The opening scenes are a smorgasbord of modern art motifs. I find them unsettling, and they don't do a thing for the film, except worry your eyes. Just fast-foward past them. Otherwise, you will have to look at a bloody sheep's head, corpses lying in a morgue, or a Buddhist monk immolating himself—just Bergman letting everyone know it's a modern film.

He filmed Persona in black-and-white, which probably surprised many people, and the style of the film contains the hard edges of earlier Expressionist films like Metropolis and The Third Man, that I discuss in earlier posts. Black and white works for Bergman the same reason it works in the earlier films. It makes the shapes sharper, the shades shadier.

In one absolutely stunning scene, the psychiatrist tells the actress that she understands the actress's basic lack of naturalness--the feeling of disgust that occurs whenever she speaks. So she just stops speaking. Persona shows the risk that acting poses for people. The actress follows the axium, "life is a stage." She basically fakes everything she does—orgasms, laughter, crying, bitching. Everything is tinged with method and artifice. After a time, an actor no longer looks at acting as a job. It gives his life reality. It is easier to act than to live. If you take away the actor's script, you deprive him of needed identity, and he will go silent. And again, if a nation does not give its people orientation, the same will happen to them.

Persona touches deftly on my personal pet-peeve, the need to divide our nation in order to save it, while the time remains to do it peacefully. One human quality that will determine if we can pull it off is ego-strength. Just the word "ego" gets a bad rap in left-wing circles; so do not count on the Left to push a division, no matter how bad things get!

So the Republicans will have to finesse it. Do we have enough philosophical orientation to understand the differences in our way of life? Do we have enough confidence in our point-of-view to withstand interrogation and disapproval? How interesting that artist-types in the twentieth-centrury like Bergman worried over these very questions, unware of the political ramifications.