The Writer as Prostitute

My pride and joy, published 2007

Every writer dreams of a movie deal. Can his writing persuade financiers to secure the rights to his book? But what will the film-director do to his story--his pride and joy? Some film-makers, like Sidney Pollack, treat the source-writer like a prostitute. He pays the writer lots of money, then treats his pride and joy with callous disregard—as Pollack did with Six Days of the Condor. He also re-wrote John Grisham's The Firm—causing presumably great anguish for the writer.

You have to ask yourself, why go to all that trouble—buy the rights to a novel, then write your own plot to it? Pollack could write his own story, then sell the rights to the movie-production people and pocket money at both ends when he directs it. The answer may be that the film-maker prefers to use a "name" writer as a vehicle for his own ideas.

writer J. D. Salinger

In The Catcher in the Rye, the narrator Holden Caulfield complains that his brother, known only as "D.B.", prostitutes himself in Hollywood, writing screen-plays. Holden actually refers to D.B. as a "prostitute," and adds, "If there's one thing I hate, it's the movies. Don't even mention them to me." Holden's opinion probably reflects that of his creator, J. D. Salinger. Salinger likewise hated movies because Hollywood turns a writer into a prostitute. You might as well sell your soul to the Devil, if you do a deal with movie-people.

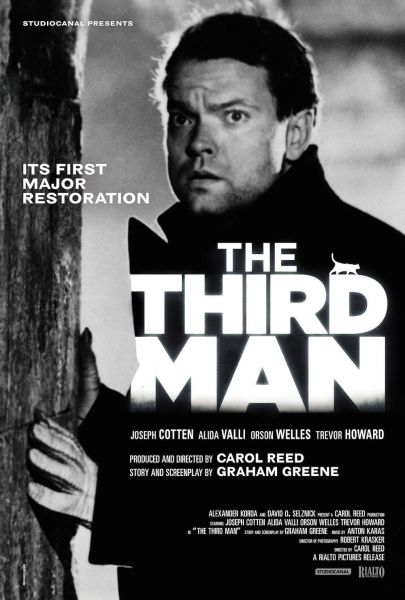

Orson Welles as Harry Lime

I recently read Graham Greene's book The Third Man for about the fifth or sixth time. In the Preface, Greene insisted that he did not write The Third Man as a novel but a screen-play, which struck me as odd. Why does a reputable writer stoop to the level of script-writer? They're nothing but dime-a-dozen prostitutes. Greene explains that Carol Reed, who directed The Third Man, asked him to write the script for it. Greene even suggests that the basic plot-line came from Reed, not from him. Greene's fond dedication of the book to Carol Reed speaks of their friendly collaboration. Neither of them had any idea that the script would turn into such a classic, succeeding both as a movie and a novel.

For me, The Third Man, works best as a novel; but the on-line encyclopedia Wikipedia took Greene's Preface at face-value and published an article only for the movie—even if Greene did work mainly as a novelist, and even if The Third Man is arguably his greatest work. It has gone through numerous editions, and its structure and first-class prose identify it as a classic.

Third Man takes place in Post-War Vienna, Austria, about 1947, as the Post-War period gives way to the Cold War. But it actually concerns an American named Rollo Martins, an unrepentant hack-writer who uses the nom de plume Buck Dexter. He tires of his prostitute-status and impersonates a real writer during a book-signing—a "name" author from Great Britain, Benjamin Dexter. Rollo succeeds with his ruse by signing "B. Dexter" on the other man's books. He does not get away it completely. Mr. Crabbin, who hosts the book-signing, has an inkling Martins should not be there. Also, the "name" author Benjamin Dexter probably would not take kindly to Rollo borrowing his feathers, just for the privilege of drinking the good coffee offered at the book-signing.