The new Hollywood of the 1970s

Hollywood's Venture Capitalists

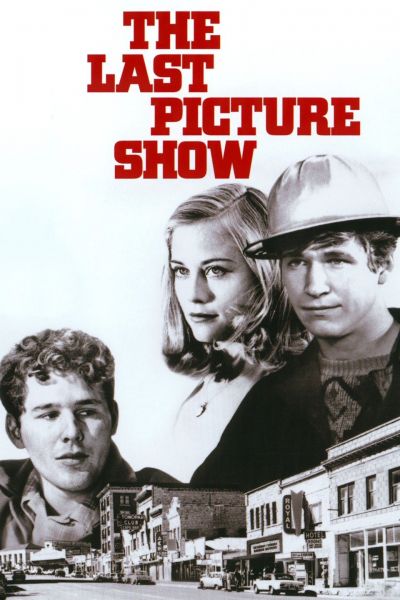

During my college years in the early 1970s, everybody was raving about a new film, directed by someone with a funny foreign name, Peter Bogdanovich, called The Last Picture Show, that starred Jeff Bridges and Cybill Shepherd, two unknown actors at that time. The critics hailed it for its realism, understated drama, and its portrayal of people living in a sad little town, Anarene, in semi-arid northern Texas—a town and people with no future. Northern Texas gets a decent amount of rainfall, but director Bogdanovich makes it look as windy and dusty as a desert. He filmed it in black and white, accenting the region's sterility and the colorless life.

The Last Picture Show deals with several thwarted romances, the lost hopes of some of the townspeople, and if that isn't bad enough, the backbone of the little town, Sam the Lion, the owner of the only cinema, dies in the course of the movie; so the cinema has to close. The restless young people await the day that they can escape—defeated on their home turf. The other characters remain, as if in a dead zone.

Walking out of the movie theatre, I carried some of the ambiance from Picture Show with me, trying to shrug off the feeling of defeat in my own life. Since then, I have wondered why anyone would bother to make such a film? You watch movies hoping for a revelation, an insight reinforced, or values confirmed; but I remember Picture Show mostly for its unrelenting negativity. Nobody in Anarene seemed to have any hope at all for the future.

The author of, novelist Larry McMurtry, who wrote the plot for Picture Show turned the misadventures of this little town into a national tragedy by showing toothless old people, unfaithful spouses, restless kids, and no redeeming values—and God it looks so dull, you want to take a tractor and push the whole kit and kaboodle into the river. Make your plans for the future with someone else's game-plan.

The next film that I saw actually pre-dates Picture Show by three years—Easy Rider. I liked Easy Rider more than most movies I had previously seen—James Bond, Walt Disney, and Alfred Hitchcock included. and I enjoyed it on different levels. I enjoyed its rock anthems by Jimi Hendrix, Steppenwolf, and the Byrds; its ambiance of casual sex and drugs, and two nice customized Harleys, paid for with proceeds from a dope deal.

The movie also has the requisite negativity. The two main characters, played by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, ride their Harleys care-free through a number of human situations that would have exerted a hold on most guys: pretty girls, available dope, pretty, natural settings—perfect habitat for the counterculture, but none of that works on the lead characters. They bank all their hopes on the drug-money. It tells a viewer something about their habitual rootlessness.

The movie ends tragically when rednecks in the lowlands of Mississippi or Alabama gun them down in a drive-by. Not surprisingly, the original title of Easy Rider was The Loners—less countercultural and more existential.

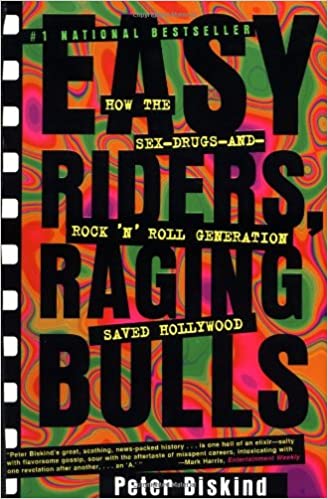

Dennis Hopper also directed. Peter Biskind writes in his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls that Peter Fonda's sister Jane tried to persuade a fellow-actor Bruce Dern to see the movie. Dern retorted, "Whaddya mean, a biker movie? We've made all the biker movies. I did eleven of them. It's over for biker movies."

"No," she said, "This one's different."

And she was right. I didn't know it at the time, but Easy Rider and The Last Picture Show ushered in a whole new genre of films, now recognized as "New Hollywood" films. They earned that distinction when the directors stepped away from the studio system and went with venture-capitalists who fronted the money but did not interfere during the filming.

The directors Hopper, Fonda, and Bogdanovich gave up on the studios because they gave them no support. They approached Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson who gave them enough money to start filming. Schneider and Rafelson made a huge investment in unknown directors and the no-name actors. Bogdanovich had done only one low-budget film before he took on Picture Show, and Hopper had only a checkered career as an actor. The investment set Schneider and Rafelson back hundreds of thousands of dollars, but they had an eye for talent, they had the nose to spot a winner, and they knew how to crunch the numbers. Those qualities earned them millions of dollars. They owned most of the "points," after all—movie-talk for shares of ownership. The more money their movies made, the more money they took home.

Francis Ford Coppola, another member of the New-Hollywood set, saw executives from the studio jerking around his friend George Lucas (Star Wars). When the studio refused to move forward on Lucas's movie American Graffiti, Coppola called their bluff and offered to buy the movie from the studio, so that Lucas could do it the way he wanted. Lucas never forgot this quixotic act of friendship, but the New Hollywood directors let the creative freedom affect them in a way no one would have expected. The money led them into an extravagant egotism.

Bert and Bob

The movie Diary of a Mad Housewife came out in 1970. It tells the story of a young couple living in New York City and their circle of friends. Like Easy Rider and The Last Picture Show, Diary is a New Hollywood film. It leaves a viewer depressed at the profound and complex negativity that hangs over everything. It has an impressive ambiance, nevertheless.

One scene in the movie has always impressed me. George Prager (played brilliantly by Frank Langella) comes on to Tina Balser (played by Carrie Snodgress) the hostess of a loud party. He says to Tina, "I noticed that you've, uh, been hanging around this doorway all evening long, and I wondered, did you happen to see a tall, skinny blond with horn-rimmed glasses come in and go out?"

"What makes you think I've been hanging around this doorway all evening?"

Prager glances around. "Is there anybody else here with an Aborigine hairdo?"

Tina tells him that she has not seen a tall, skinny blond. George seems skeptical, then smiles with amused contempt and nods his head slightly. He seems satisfied with his appraisal of her. "How old are you, 28, 29?"

"It's none of your business," she hisses.

"Easy, baby, easy. You're in terrible shape."

"Why are you cross-examining me?"

"Are you interested in my answer? . . . It's too bad you're not my type."

Anyone versed in New Hollywood films knows to expect the unexpected. Prager and Tina Balser have an affair, even though she is married and can meet Prager only when her vain, self-centered husband is away—which thankfully is often—and even though Prager treats her with cold derision.

Perhaps someone will write a tell-all about this movie and admit that George Prager is based on Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider's partner. Peter Biskind's history of the two men define them pretty well: "Rafelson was handsome in the Jewish way . . . rosebud lips under a fighter's battered nose.

He was tall, thin, and powerfully built—coiled so tight, he seemed to vibrate. There was an intense brooding quality . . . and a cruel, predatory streak that could be attractive."

Bert Schneider had the same predatory streak, Biskind writes. "Bert was so relentless that he came on to almost every pretty woman who came his way," even though, like Rafelson, Bert was married. His wife Judy had to put up with a lot. Biskind relates how Bert "began to make fun of Judy's bourgeois refinements (and) liked to rattle her cage with real or contrived vulgarities."

Anyone who visited Bert and Bob's office got to know them pretty well. Their "style of discourse was brutal. Half-playful, half-hostile . . . Bert in particular had a gift for nailing people at their weakest point, and he would take no prisoners. If they failed to respond in kind, showed fear or anger, or worse, were intimidated into silence," Bert bore down on them.

Even more importantly, Biskind writes that "When Bert made an entrance, it changed the chemistry of the room. He had the charisma of a movie star. It was not just looks; he was possessed of extraordinary personal authority."

Biskind writes something interesting about the ethos of Bert and Bob, that they were "invested in being hip, looked to black people . . . for validation, the kind of person for whom (Norman) Mailer's essay 'White Negro' was written."

Wikipedia has posted an interesting article about "White Negro" declaring it "a call to abandon Eisenhower liberalism and the numbing culture of conformity . . . in favour of the rebellious, personal violence and emancipating sexuality that Mailer associates with marginalized black culture."

Mailer advises white men to engage life as "someone living for the primitive present and the pleasures of the body." Whites need to respond to the "burning consciousness of the present."

"White Negro" gets scary in places. The "hip judgment of character" is "perpetually ambivalent and dynamic." Men should be governed by "an absolute relativity where there are no truths, other than the isolated truths of what each observer feels at each instant of his existence." In short, it's the law of the jungle, the key to gaining power over everyone else.

One has to wonder if they saw any conflict between their business-like approach to doing movies and their "white negro" stance. It is significant, I think, that both Bob and Bert participated in left-wing causes. "Bert was mesmerized by Huey (Newton, the Black Panther)."

"How can I put it?" Bert asked. "He's my hero. If he's not Mao, I'll eat it."

Biskind writes that many saw "Schneider's infatuation with Huey as the worst form of radical chic." He also quotes the actor Buck Henry: "Huey served the sense of these guys' embarrassment, about where they came from, and what kind of privilege they received."

Bert's infatuation with Newton culminated in his effort to help Newton flee to Cuba, in order to escape prosecution for killing a teen prostitute, but the boat Bert obtained sank; so his friends drove Huey to Mexico.

Perhaps Bert's involvement in Peter Davis's 1975 documentary Hearts and Minds expressed his left-wing stance the best. Heart won the 1974 Academy Award for best documentary, but his acceptance speech scandalized the Academy: "It is ironic that we here at a time just before Vietnam is about to be liberated." Bert meant, of course, liberated from the American military. Most of the guests clapped; others hissed their contempt and rage. Bert's smirking smile did not help matters.

Francis Coppola

"Imagine, 1975, getting a telegram from a so-called enemy extending friendship to the American people. After all we did to the Vietnamese

people, you'd think they wouldn't forgive us for 300 years!"

(Francis Coppola on Bert Schneider's Hearts and Minds documentary,

quoted in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, by Peter Biskind)

Coppola made his own outrageous, left-wing statement about the Vietnam War in a landmark film titled Apocalpse Now. Movie connoiseurs, left-wing nouveau riche, and anti-war advocates applauded the movie. Curiously, the Old-Guard, left-wing publications like The Nation and The Washington Post gave Apocalypse a thudding thumbs-down.

The Post in particular shreds Apocalypse for its "ruinously pretentious" story about a West Point graduate named Kurtz (Marlon Brando) who creates his own kingdom on the Viet-Cambodian border. It "recalls nothing so much," writes the reviewer, "as the notorious campfire scene in Mel Brooks' Blazing Saddles," where aged cowboys sit around a campfire, eat pork and beans, and fart continously.

The Post also skewers the scene with Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) on the river, calling it a "conceptually preposterous episode, it nevertheless provides spectacular cinematic sport." The Post describes Kilgore—as the name suggests, "kill-gore"—a "cheerfully brutal cavalry officer who bombards a coastal village because he hears the surfing is great there."

"As idiotic as this airborne assault is," The Post concludes, "it sums up whatever point the filmmaker has to make about wanton violence in Vietnam."

Biskind writes about Apocalypse Now that Coppola went through so many personnel changes at the supervisory level, his core ideas of the movie must have evolved over time. At the end of the changes or incarnations, all that remains of Apocalypse is an unfocused or sketchy comic-book fantasy enabled by drug-use or personal cynicism. It detracts from the outrage a viewer might expect to experience from the gratuitous violence committed by American soldiers on Vietnamese civilians.

No one doubts the sincerity of Coppola's left-wing convictions; but even in the Post, he is described as a "feckless Hollywood liberal," who thinks of himself as an "anti-war moralist and stern foe of American imperialism." Biskind describes his political views as "schoolboy Marxism (He always equated the mob with capitalism.)"

Biskind also quotes one of Coppola's enemies at Paramount Studios, who sneered, "'Poor little me. All I wanna do is make my films . . . fly on Learjets and use stretch limos.' (Coppola) was a true Mercedes Marxist."

Coppola reminds me of John Lennon, who was also a fiery, driven leftist, beset by doubts of authenticity at his most personal level; and like Lennon, Schneider, and Rafelson, Coppola had numerous affairs—carrying on with women in the open while married to Eleanor. He just humiliated her.

Like Schneider and Rafelson, Coppola subscribed to Mailer's "White Negro" rebel, driven toward sexual liberation and a relativist, or self-serving, stance on moral issues, to enable his drive to power.

The Adventure of Freedom

The phrase "the adventure of freedom" comes from a sub-title in Wikipedia's article about Friedrich Schiller's play The Fiesco Conspiracy, which Schiller wrote in 1782, while on the run from royal authorities in Stuttgart. He stopped in Mannheim to finish the play, to show it to a few people, and to get production support for a staging of the play, a situation not dissimilar to the New Hollywood directors.

After German Unification in 1871, both cities became part of the new Germany, but before that, Stuttgart had been a city in the kingdom of Württemberg, and Mannheim a city in Rheinland-Pfalz, called in English "Rhineland-Palitinate," both in southwest Germany. The authorities in Stuttgart issued a warrant for Schiller's arrest, but it had no extradition treaty with Mannheim; so Schiller could live safely among his friends and admirers, for the time being, and finish The Fiesco Conspiracy.

The play takes place in Genoa, Italy, in the 16th century, when Genoa was known as the Republic of Genoa, a city-state ruled by a Doge, or chief magistrate, a member of the nobility. It had a government more or less alien to our own, with an absolute ruler who provided city services, and established basic civil rights. Genoa also promoted commerce, which allowed upward mobility, and a chance to become wealthy; but the Doge ruled arbitrarily. The public had no recourse over his administrative decisions. If pressed, the Doge could squelch dissent harshly, and citizens could lose their lives or citizenship.

The 80-year-old Andrea Doria has governed Genoa for nineteen years, but people in Genoa fear that he will promote his criminally-minded son Gianettino to become the next Doge. Gianettino has already raped a woman and compiled a hit-list of people he wants to eliminate when he takes power. Some of the conspirators already know their names are on that list, so they decide to take action.

Giovanni Fieschi (Fiesco's real name, pronounced "fee-esky") suspects his name is also on it, so he takes the lead role in a conspiracy to oust the Dorias and prevent his son Gianettino from succeeding him. The other conspirators do not fully trust Fiesco. They want to retain the republican form of government and sense that he will assume power to rule in his own name.

On the one hand, Fiesco says, "Perish, tyrant! And I, your happiest citizen!" But the next moment, he says longingly, "I, the greatest man in all Genoa? Shouldn't people with small minds gather around great minds?"

The conspirators follow through with the plot and murder Gianettino. Fiesco's wife foolishly puts on Gianettino's scarlet cloak, signifying his noble status, but she also is murdered in the general melée. Fiesco puts on the cloak and presents himself to the people of Genoa, who joyously receive him as their new duke.

Schiller describes him as "the empty, smiling expression of a good-for-nothing, while raging wishes ferment in his breast. Long enough misunderstood, he finally emerges like a god to present his mature and masterly work to an amazed public." Fiesco is, comments Wikipedia, "a person of overwhelming inpenetrability, who is so free that he incorporates both possibilities, a tyrant and a liberator from tyranny."

But the story has more complexities than that. Wikipedia writes about Scene Eight in Act Two, the "crowd" scene. A group of men tell Fiesco they do not want an arbitrary Doge. Beyond that, they really don't know what they do want. "In their perplexity," Wikipedia writes, they turn to Fiesco, to "rescue" them. He persuades them to give up their wish to establish a democracy, saying that it is the "rule of the cowardly and stupid."

Fiesco puts on the scarlet cloak, impressed at how good he looks with it. One of the republican conspirators begs him to take the cloak off—thus rejecting the absolutist leadership that the cloak symbolizes, but Fiesco refuses. The conspirator goes down on his knees and begs, but Fiesco again refuses; so the conspirator decides he can no longer trust Fiesco. He fears Fiesco could become an even worse tyrant, and murders him. Then he says that he will go to Andrea Doria to tell him that the conspiracy has failed and that Andrea Doria should stay in power.

It is curious that this play caused such an uproar in Schiller's day, since by the end of the play, the Republic of Genoa is back to where it started, with Doria still in place as its leader; but the impact of the experiences resonate in the reader—the inherent risk of an absolutist leadership, the hunger for political freedom, and the hassle of dealing with human personalities. It is definitely a drama for our time.

How We See Ourselves

"There was a real contradiction in what we perceived ourselves

to be doing and what in fact we were doing." (actress Margot

Kidder, quoted in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls)

The Fiesco Conspiracy reveals a few human insights that we should not ignore; that wealth and power make us free. The two assets also help us express our inner-selves better than psychoanalysis or bio-feedback. For most people, the expression of our inner-selves reveals a complex ambiguity—our feelings toward others, our views of ourselves, and our basic motives. Our intentions splay into many strands of reasons, going this way and that.

It also says to me that nature hard-wires a neurological governor into the psychology of people. They work hard all our lives to acquire money and power, and those assets give them a level of freedom that other people can only dream about; they also reveal a vacuum of selfhood, contradictory impulses, and a benighted search for meaning in life. It can take strange directions, which thwarts man's temporal ascendancy.

Nothing reflects that better than the New Hollywood film-makers. To quote the old saying, “They had it all.” They revelled in the freedom to create, and they all turned Marxist. They made heaps of money and used it to support causes that, if successful, would take their money away, again.

Coppola supported left-wing causes, but he did not allow his own production crew to unionize. He opposed the concentration of power wielded by business-leaders and Republican Presidents, but he became an empire-builder in his own right. Biskind relates two stories about Coppola on this point. In one story, Coppola gathered his staff and subjected them to a wild harangue lasting several hours. “He . . . started to talk about taking over Hollywood, building an empire.” People said he was out of his mind. But not long after that, his friends threw a birthday party for him and shouted, “We will rule Hollywood! We will rule Hollywood!”

Biskind relates another story about Coppola talking to a journalist. Suddenly, he fell to his knees before a “pyramidal skyscraper that poked upward through the skyline of North Beach. It was the Transamerica headquarters.” Transamerica owned the studio of United Artists. Coppola already owned the Sentinel Building across the street, but he bellowed at the Transamerica building, “Someday, I'll own you, too!”

Copolla had the same effect of people that Fiesco had. He enthralled some, alienated others. He aroused suspicion about his real intentions, exuding the same ambiguity as Fiesco. George Lucas, director of the Star Wars films, told Biskind that Coppola “has charisma beyond logic. I can see now what kind of men the great Caesars of history were, their magnetism.” Biskind adds that Coppola “surrounded himself with true believers who job it was to serve Francis and his vision.”

Other Democrats should take note of his contradictions and ambiguity and understand the risks that people like Rafelson, Schneider, and Coppola pose for them, instead of joining their entourage.