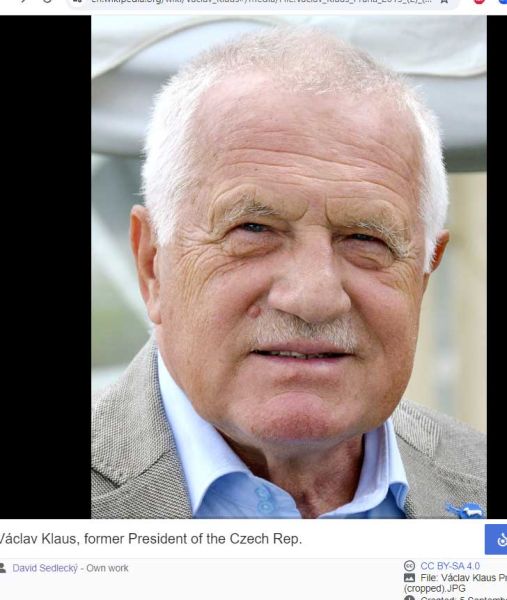

Vaclav Klaus and Nationhood

Hardly any Americans remember this remarkable man, but he took over the leadership of the old, post-Soviet Czechoslovakia, in order to push it toward a Western-style democracy with a modern market-economy; but released from its Soviet yoke, the Czech-Slovak nationalistic rivalry that had existed before the World Wars came alive again and created political instability and public anxiety. The rivalries threatened the future of the nation and its ability to grow and prosper.

Klaus wanted the Czechs and Slovaks to let him to turn Czechoslovakia into a federal republic, to give the government more power to override the rivalries. When the Slovaks said they wanted a confederation-type government, Klaus decided to push for the division of his country. This action has caused modern-day Czechs and Slovaks to view him with mixed feelings, perhaps because he and Slovak leader Vladimir Mečiar did the division as a top-down action, with little participation from the public.

Before the division, Czechs and Slovaks viewed each other with suspicion, concerned that one or the other nationality would try to dominate the national government and put its own interests above the other's. Klaus decided Czechoslovakia needed a stronger, federal structure. or else it needed to divide. Factions within the Czech and Slovak communities said they wanted a confederation, that allowed them more autonomy, but Klaus did not.

I am certain that Klaus must have studied American history and already knew how poorly America had governed itself as a confederacy, from 1783 to 1787, under the Articles of Confederation. He must have also known that America's Founding Fathers ratified the U.S. Constitution as a top-down action, and recognized that his own nation needed the same centralized functions, for efficiency's sake; but a division of the nation entailed a huge risk. Even today, no more than 35% of Czechs and Slovaks approve of it.

I, as an American, approve of what Klaus did and believe that if little Czechoslovakia can pull off a division and prosper, then the great-big USA should prosper, as well. Americans have forgotten that Klaus's rival, the author Vaclav Havel, wanted a socialistic model of government, but instead Havel resigned from the government.

I will hazard a guess that the Czechs and Slovaks disappointed Havel, inasmuch as they wanted nothing to do with Socialism. They had known it as "National Socialism", under the Nazis, and as "Soviet Socialism" under the Soviets, and determined that Socialism had plundered their nation, without giving much back. The "Black Hole" of Socialism drains the creative energy of a nation, in the name of equality and uniformity. Socialism is its own worst enemy.

Klaus may have guessed as much. Socialism's egalitarian ethos gives mankind's abilities a lower arithmetic-mean. In other words, Socialism does not really have a high opinion of human-kind—a human's intelligence, initiative, or problem-solving ability, if left to its own devices—and believes that mankind needs the input of government experts to direct everything.

Not surprisingly, I suppose, Klaus, the free-market economist wanted a nation that tests mankind's problem-solving ability, by allowing market-forces to prosper the economy. Acceptance of the free-market reveals a faith in mankind—to wit, that left to his own devices, he can accomplish almost anything, solve almost any problem, and create wealth along the way. America, the perennial, social test-tube nation, proves this every year. People from around the World struggle to get here to enjoy its fruits.