Wikipedia and History-AIDS

World Epidemic-2020

There can be no doubt that the Covid-19 epidemic has been the shock of our lives! With pharmaceuticals, sanitation, and nutrition on our side, how could this happen? We humans thought we were close to invicible. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the deaths of 3,500 Americans also ranks very high in shock value; but the Covid virus killed an average of a thousand Americans every day from mid-March until the middle of the summer.

My hometown Charleston practically shut down during the Spring. No one went to work, the schools closed, and the empty downtown streets filled up with rollerbladers, cyclists, and skateboarders, cruising triumphantly the urban void. Most businesses closed for two months. Many could not afford to close at all and closed permanently. Only grocery stores and pharmacies stayed open. Panicked shoppers routinely bought out supplies of toilet paper, thermometers, and over-the-counter medications.

Journalists, politicians, and other public servants have, so far, issued mostly muted blame and criticism for the spread of the Covid-19. In general, the Trump administration blamed China; the Democrats blame Trump. The rhetoric falls into the mold of predictable, polarized reactions, as it does on most important issues.

Americans try to keep life tolerable in the context of their day-to-day routines, disregarding media efforts to overinform them on every issue, from fast-food to asterroid showers. If Americans ignore the media's warnings about Covid-19, the media really has no one but itself to blame, for routinely jacking up the public stress-level and making us cynical about every revelation.

To think Covid has spread so rapidly—a world epidemic in two or three months! First in the Orient, then Europe and Iran, then the U.S., and now increasingly in developing-nations like India and South America. How mobile modern-man has become! This no doubt has helped the virus spread quickly. If asked, public leaders will probably also admit they underestimated its contagiousness.

Hopefully we will soon see a downward curve for Covid-19, both in the rate of transmissions, and eventually in the number of deaths, too. After the scientists start mass-producing a vaccine, then perhaps the criticism will increase: why the scientists couldn't find a vaccine sooner; why one group gets the vaccine sooner than another; and why the vaccine costs so much. If we can escape Covid-19 without serious economic repercussions, we will really dodge a bullet.

WORLD EPIDEMIC-1980

Covid-19 is actually the second global epidemic that I have experienced during in my lifetime. The first epidemic, the AIDS epidemic, appeared in the 1980s, the first global illness the world had experienced in many years. Like most people, I hardly paid it any attention. I rarely watched TV news or read newspapers. The deaths of a few celebrities and former college classmates finally brought it home to me.. I was working 50-hour weeks in my father's decrepit livestock-feed mill and enjoying an active social life. My new car gave me the mobility I needed.

While Covid-19 fooled people mostly with its high contagiousness, AIDS kept doctors and scientists in the dark for a number of reasons. First, it could lie dormant in the human body for months. When finally it revealed itself, it did so in the guise of exotic, unrelated, secondary illnesses that the doctors had never heard of. The secondary illnesses did not normally kill people; so why did most of the patients die? The doctors did not have a clue.

Most of the patients lived in San Francisco and New York, and most of them were homosexuals. At first, when the exotic illnesses appeared, the patients' sexual orientation did not appear to have any bearing. The frontline doctors who had to deal with the medical mystery deserve a lot of credit for alerting the medical establishment and the public.

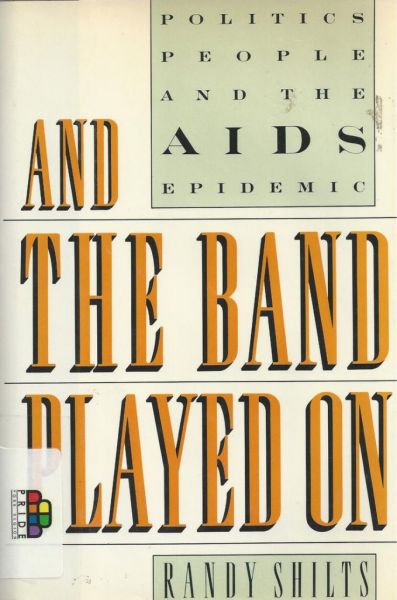

Anyone interested in learning more about the origins of the AIDS epidemic should consider reading And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts. He worked as reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle and published And the Band Played On in 1987, before dying himself of AIDS in 1994. He chronicles story from its beginning in 1976 with the curious illnesses of Margrethe Rask. Rask was a Danish doctor who worked in a mission hospital in Kinshasa, Zaire. Dr. Rask grew thin and weak and could no longer carry out her duties, although no one could figure out what made her sick.

She returned to Denmark and died in 1977 of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Her doctors could not undersand why she had this illness, much less why she died from it. Healthy people in Western Europe hardly ever got Pneumocystis pneumonia. It was so rare, her doctors had to look it up in a tropical-disease handbook. They have since concluded that she infected herself with AIDS by handling patients with her bare hands. Her hospital never had enough surgical gloves.

In my website-post from 12th August, I discuss the work of historian Allen Weinstein in revealing the truth about the Alger Hiss Case. He had the advantage of access to the files of Hiss's attorneys, who had kept excellent, detailed records. When the journalist Randy Shilts started researching AIDS, he consulted the frontline doctors, who dealt with the first cases.

Doctors, like lawyers, keep excellent records. Like Weinstein, Shilts relied on the doctors' files for his story. He spent days rummaging through reams of prescription records, medical charts, correspondence, and memoranda. Writing a comprehensive history of an epidemic presented a host of challenges for Shilts, but the office-files give Shilts a first-hand account . They eyewitness the telling of the AIDS story with a welcome transparency.

The doctors were the first to pick up indications of a larger problem behind the outbreak of exotic illnesses. They had a time trying to persuade governmental agencies and medical foundations that they were not quacks or self-promoters, and that the agencies with the big research-money needed to get involved. It gets a reader down to consider the obstacles the doctors faced, but Shilts explains why the snafu happened.

Government agencies had to decide which agency had primary responsibility for the illness. And there you have to ask "Which illness?" Pneumocystis Pneumonia, a pulmonary disease? Kaposi's Sarcoma, a skin cancer? The intestinal parasites? Each disease had a different agency responsible for it. If they were parts of a protean epidemic, that could be a problem. Was the illness infectious? Maybe it was sexually transmitted. Maybe the pneumonia came from recreational inhalants popular in gay discos. If patients suffered from Kaposi's Sarcoma, shouldn't the National Cancer Institute handle it? If the illness was infectious—passed by patient-to-patient contact—the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease should take the lead. Success in fighting the diseases depended a lot on friendly contacts between the many organizations of America's vast medical bureaucracy, and dealing with doctors and government officials whom no one had ever met.

Nowadays, you can go on-line and hire professionals who do nothing but write grant-proposals. A grant-proposal can help you contact a private foundation for financial help. But who would you go to in the case of AIDS? A foundation rep will want to know what the illness is, and all you can tell the rep is that the illness appears as a bewildering variety of secondary illnesses, and that something more fundamental causes them, but you don't know what.

The incompleteness of the doctors' knowledge—with the many lives hanging in the balance—left the frontline doctors feeling scared and helpless. Shilts learned enough about the exotic secondary illnesses to , like Kaposi's Sarcoma, Pneumocystis Pneumonia Carinii, and Cytomegalovirus, which did not normally kill people. Something else made them deadly.

The Touchy Issue of Responsibility

As the doctors and researchers learned a bit more about the new epidemic, they gave it new names. It started out as the "gay-cancer" or the "thin-disease." Then it became GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), then the generally accepted acronym AIDS (Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome), and finally its epidemiological moniker HIV1.

The subject of how AIDS spread so quickly has become a political football, kicked around like all political footballs, on the scantiest evidence. Fortunately Shilts consulted the files of the frontline doctors. Often, the doctors had to make the judgment-calls for their patients, when they could not see past the symptoms of the secondary illnesses. One can only laud them for their efforts.

So who can we blame? People want to know how a virus can spread so widely before the authorities start engaging it. Who could we hold most responsible for allowing AIDS to spread? Even a casual observer can see the difficulty of determining that.The ability of AIDS to incubate for months, then masquerade behind secondary illnesses, meant that many people had already contracted it before anyone grasped the scope of the problem; but principally AIDS started among gay men in large cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. As diseases go, AIDS was in the right place at the right time.

Gay Liberation started in the 1970s as a protest against police crackdowns and the Christian Right. It gained a sort of flamboyant stance in the late '70s, but the Gay movement disliked negative publicity and interference from the wider society. As it became more visible, however, it attracted more press attention anyway, especially after researchers identified the early AIDS cases with Gay bathhouses and discos.

The gays did not hide their hedonism. They epitomized the culture of sex, drugs, and disco in the 1970s. A migration of homosexuals to large cities at this time brought many of them together. After suffering alienation from their peers in the provincial social environment of their hometowns, they migrated by the thousands to places like the Castro District in San Francisco. The Castro District had the same cachet that Haight-Ashbury had in the 1960s, as the home of the hippie movement.

Some expressed reservations about this new gay hedonism. The writer-activist Larry Kramer, for instance, wrote up his concerns in a novel Faggots that he published in 1978. Shilts knew Kramer and includes quotes from Faggots. "Why do faggots have to fuck so much?" Kramer wrote. "It's as if we don't have anything else to do . . . (but) live in our Ghetto and dance and drug and fuck." The man character in Faggots, Fred Lemish, is a 39-year-old Jewish man who tries to find true love in the gay-party scene of New York. The book gave Gays a more dubious reputation than they wanted.

Shilts also expressed reservations about the hedonism. He quoted the Cuban-American artist Kico Govantes, who said the hedonism reminded him of the Federico Fellini movie Satyricon, filmed in 1969 about two young men vying for the affections of a boy prostitute.

Shilts's Interviews with Doctors

Nothing, however, conveys the hedonism of the gay movement like the files of the frontline doctors who treated the very first gay patients. What Kramer described in fiction, the frontline gay doctors of San Francisco and New York saw in real life, starting about June of 1980. Dr. David Ostrow was director of the Howard Brown Memorial Clinic. Shilts studied Dr. Ostrow's files and came up with disturbing findings:

1. One in ten patients had walked in the door with hepatitis B. At least one-half of the gay men tested at the clinic showed evidence of a past episode of Hepatitis B. . . .

Another problem was enteric diseases, like amebiasis and giardiasis, caused by organisms that lodged in the intestinal tracts of gay men. . . . Infection with these parasites was a likely effect of . . . oral-anal intercourse."

2. Dr. Dan William of the New York Gay Men's Health Project told Shilts, "What was so troubling was that nobody in the gay community seemed to care about the waves of infections." Dr. William "had his 'regulars', patients who came in with infection after infection, waiting for the magic bullet." He said to them, "I have to tell you that you are being very unhealthy." His warnings however fell on deaf ears: "Promiscuity was central to the raucous gay movement."

3. Dr. William went public with his concerns in an interview published by Christopher Street, a New York gay magazine. He cited studies which showed that visitors to bathhouses had a 33% likelihood of catching syphilis and gonorrhea; but "Such comments were politically incorrect in the extreme," Shilts writes. "Dr. William suffered criticism as a 'monogamist'."

4. Dr. David Ostrow in San Francisco was likewise "haunted by forebodings. . . . (T)here would be no stopping a new disease that got into this population." Some gay men were already having problems with their immune systems. Dr. William saw "strange inflammation of the lymph nodes among his most promiscuous patients." He also recorded an examination of a patient recovering from Hepatitis B and noticed "strange, puplish lesions on his arms and chest. The man, it turned out, was suffering from a rare skin cancer Kaposi's Sarcoma."

5. Dr. Selma Dritz, Assistant Director of the San Francisco Department of Public Health took her own concerns to the monthly meeting on sexually-transmitted diseases held at the medical center on the campus of the University of California-San Francisco. She told the assembly that between 1976 and 1980, the incidence of dysentery among single men between the ages of 30 and 40 had increased 700%. The incidence of Hepatitis-B had quadrupled, and in most of these cases, the cause was the frequency of oral-anal sexual contact among gay men. . . ."

6. Too much is being transmitted," she said. "We've got all these diseases going unchecked. There are so many opportunities for transmission that, if something new gets loose here, we're going to have hell to pay." Dr. Dritz told Shilts.

7. Gay men were being washed by tide after tide of increasingly serious infections. First, was syphilis and gonorrhea. Gay men made up about 80 percent of the 70,000 annual patient visits to the city's VD clinic. Easy treatment had imbued them with such a cavalier attitude . . . many gay men saved their waiting-line numbers, like little tokens of desirability. The clinic was considered an easy place to pick up both a shot and a date.

8. Gradually the efforts of the frontline doctors convinced government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to get involved. Shilts writes that CDC personnel did not particularly care for the work: "The next weeks were spend acculturating the CDC field staff to the complicated gay sexual scene." When told that many of the gay men had had as many as 2000 sex partners, the staff could hardly take it in: "How on earth did they manage that?"

9. Dr. Mary Guinan worked as an epidemiologist for the CDC. With only a modest expense allowance, Guinan had to start tracking down the origins of the illnesses. It must have been unsettling to walk into gay-porno shops, look at recreational inhalants, and ask the gay men about their personal lives and private habits. On July 17, 1980, she interviewed Gaetan Dugas, a Québecois who worked as a flight attendant for Canadian Airlines. He had lived a very fast life, His story to Guinan became the norm. Nearly every doctor Shilts interviewed had a story about Gaetan Dugas, or else someone like him.

The Debate over Gaetan Dugas

"It had been a standing joke," friends of Gaetan Dugas told Shilts:

Gaetan Dugas would walk into a gay bar, scan the crowd, and announce to his friends, "I am the prettiest one." Usually his friends had to agree.

They attended the crowded discotheque at the Galleria Design Center in San Francisco and danced for hours, fueled by cocaine, qualudes, and recreational inhalants that were a staple of such parties.

Dugas's friends told Shilts that he kept a notebook full of the names of his former lovers, but when they asked him about his lovers, he told them he could not remember much about them. For a few days, they were "wonderful and sexy." Then he went on to new destinations with his job and forgot about them. Thanks to his mobility, many people knew Gaetan Dugas:

1. Guinan told Shilts that Dugas "had been quite sexually active. . . . The French-Canadian had a sex life much like that of the other gay men Guinan had interviewed. Including his nights at the baths, he figured he had 250 sexual contacts a year. He'd been involved in gay life for about ten years and easily had had 2,500 sexual partners."

2. Dugas had purplish blotches on his skin and asked the doctor to remove them for cosmetic reasons. The doctor who examined him later told Shilts that he had had a time trying to identify the blotches because he had never seen them before. They were Kaposi Sarcoma lesions, a skin cancer that no one had seen for years. People in the poor regions around the Meditarranean Sea occasionally contracted it earlier in the century, caused by poor nutrition; but no one had seen it in years. Dugas also had swollen lymph nodes and didn't know why.

3. Eventually Dugas's flamboyant, promiscuous lifestyle caught up with him. Dr. William Darrow of the CDC called on a hairdresser with AIDS who lived outside Los Angeles. "I bet I know how I got this thing," he told Darrow. "I had sex with this attractive guy I had met at a bathhouse." The man thumbed through his address book. "Gaetan Dugas," he said.

CDC officials already knew the name:

4. The connections started falling into place. Of the first nineteen cases of GRID in Los Angeles, four had had sex with Gaetan Dugas. Another four cases, meanwhile, had gone to bed with people who had had sex with Dugas, establishing sexual links between nine of the nineteen Los Angeles cases.

5. Dugas was unrepentant. After another examination, Dr. Marcus Conant mentioned that he should stop having unprotected sex. "If you do have sex, make sure to avoid . . . body fluids."

"Of course I am going to have sex," Dugas retorted. "Somebody gave this thing to me. I'm not going to give up sex."

Dugas was a man of his word. He did not stop having unprotected sex. Two years before he finally died of AIDS, the doctors of the CDC assessed his role in spreading the illness:

1. By the time Bill Darrow's research was done, he had established sexual links between 40 patients in ten cities. At the center of the cluster diagram was Gaetan Dugas, marked on the chart as Patient Zero of the GRID epidemic. His role was truly remarkable. At least 40 of the first 248 gay men diagnosed with GRID in the United States, as of April 12, 1982, either had had sex with Gaetan Dugas or had had sex with someone (else) who had.

2. Dugas frequented bathhouses, and "he was the type everyone wanted." Dr. Marcus Conant thought, "He might be there now. . . . People could be out there catching this now."

Dugas accepted his role. Shilts writes that he "confided to a few friends that he was the 'Orange County connection,' as the study became known, because of Gaetan's role in linking the New York. Los Angeles, and Orange County cases." Dugas's life turned darker as the disease took its toll on him. Shilts writes that:

3. Rumors began about a strange guy . . . a blond with a French accent. He would have sex with you, turn up the lights in the cubicle, and point out his Kaposi's Sarcoma lesions. "I've got gay cancer," he'd say. "I'm going to die and so are you."

4. Finally, Dugas's friends told Shilts that his "sexual prowling had reached legendary proportions," and "he made little effort to conceal his medical problems." Dr. Conant concluded that Dugas "was a sociopath driven by self-hatred."

Wikipedia's article on Dugas disputed the reliability of his designation as the "patient-zero" of the AIDS epidemic, but the dispute lacks the weight of Shilts's research and the cooperation of the frontline doctors. Wikipedia disputes the designation on the basis of a typographical error--"patient-O" because he came from outside California, not "patient-zero."

The "Patient-Zero" designation might fit someone else better—someone who infected more people than Dugas did. He was certainly not the only promiscuous Gay male. Many Gays bought into the the idea of sex-acts and sexually transmitted diseases as "revolutionary acts." The CDC doctors, who had the terrible job of following the trail of sick men to the common source in their sickness, knew that they had had hundreds, if not thousands of sex partners. Wikipedia's belittling the CDC's efforts to track the spread of AIDS leaves me with a bad feeling toward Wikipedia, not the CDC.

Dr. Marc Conant had other patients who behaved as irresponsibly as Gaetan Dugas. "Well, I'm off to the baths," said one of them after an examination. The patient waited to see how Conant reacted.

Conant was dismayed. The patient had a doctorate in computer science and a solid reputation in the community.

"When you have sex, do you tell the guy you have AIDS?" Conant asked him.

Of course he didn't, the man replied casually.

It puzzled Conant that such an intelligent guy did not mind putting others in danger. If he behaved in an irresponsible way, there had to be others like him spreading this disease. He realized that the doctors and the CDC had a problem finding a lasting solution.

The Consent of the Governed

Dr. Conant thought he had the right idea. He told Randy Shilts, "The ideal scenario would be to get the gay commuity to shut down the bathhouses themselves. Without state action, the closure could be hailed as the work of people taking responsibility for their lives."

These are high-minded words from Conant, but why else do human societies have governments and local civilian authorities, except that we benefit by having them. Human-kind works better by being organized, rather than leaving isolated individuals to decide what to do. We let organizations impinge on our individual freedoms, so that the totality works better. Organizations use people as moving parts of the social machine. We carry out our duties, the machine functions better, and everyone benefits from the coordination. Americans should recognize the utility of organization is one of the essential givens of a human society.

The Constitution undergirds the human organization. A constitutional republic moves forward with "the consent of the governed." Once in place, the governing class does its job with administration, enforcement, and the means to pay for it all. Conant's idea of "shutting down" the bathhouses, on the other hand, smacks of a moral crusade. We should know by now that prohibitions have limited success, because they simply drive the sinful enterprises underground.

The bathhouses in the context of gay liberation present a health problem, but closing them works against the idea of a free society. As an institution, bathhouses date back at least to Ancient Roman times. The city of Bath, England, possesses a Roman bathhouse. A number of towns in Germany have the name "Bad" in them to publicize their hot springs: Bad Kissingen, Bad Langensalza, and Baden-Baden. Public baths have a tradition in the human realm. No doubt, homosexuals have used them for just as long. No one should care that this happens, as long as they don't turn the bathhouses into brothels.

The secret to running a successful, law-abiding society is to allow sinful things by controlling their access and use. We have government departments that regulate consumer goods and physical areas where people congregate. We still get fires in buildings that kill people, usually after inspections have served notice of deficiencies. We still have outbreaks of food poisoning caused by poor controls in food-preparation, even with regulations, but the controls work fairly well for a huge, diverse country like ours.

Rather than close the bathhouses, you supervise them by assigning them to a regulatory agency and letting the requirements for insurance coverage, fire-safety compliance, and sanitation services do the rest. If a government simply closes a house of sin, it will move underground, and no one wants that. Keep commercial enterprises above ground to increase the odds that nothing will go wrong. If a business owner does not comply to the standards of an above-ground business, then assess fines against him to bring him in line.

Controlling the humans themselves presents a more delicate problem, especially if they do things in the privacy of their own homes; but if they want to do things in public places, then the society has to assert its authority. The law forbids bars to serve drunken patrons; nightclubs and bars limit the number of people who can inhabit the building at one time; public places must maintain emergency exits, and so on. In turn, the public places hold their guests accountable for their behavior. If they do not behave, someone will call the police and have them removed.

But in order for that to happen, the society needs political will. It needs a plan for coordinated and comprehensive standards. The politicians and administrators can only do that with the consent of the governed. The public cannot complain about the results if the administators initiate a plan, and the public does not follow it. Political will depends a lot on political unity, and we don't have much of that right now.

The Wikipedia Article: Blame the Government

Wikipedia should pull its article on And the Band Played On and rewrite it. The present one lacks the format and content of an expository article. It does little more than blame the administration of President Ronald Reagan. This tendentiousness and vindictiveness of the article overshadow the intent of the book, which was to chronicle the AIDS epidemic. It ignores Shilts's attention to detail in recalling the events leading up to the epidemic, in naming the important characters, painting the social environment in which AIDS thrived, and happily bypassing all of the complexity of AIDS as a medical problem.

It oversimplifies the epidemic with tendentious journalism, omitting the facts that don't fit Wikipedia's preconceptions. This tendency to use a scapegoat for our sins is as old as the Bible. It pains me to see Wikipedia do this in the context of a complex problem like the AIDS epidemic, with its many moving parts. "If you can't beat the horse, beat the saddle," to quote a saying from Ancient Rome. If Wikipedia can't afford to blame gay promiscuity, drug use, and indifference to their health risks, then blame the government.

The article states that Shilts placed "special emphasis on government indifference and political infighting." The truth is that, yeah, there was some indifference and infighting. Wikipedia goes on to say "Shilts's premise is that AIDS was allowed to happen." That is completely false. Not even a casual reading of Shilts's book would leave a reader with this conclusion. The personnel of the CDC spent weeks "acculturating" themselves to the "complex gay sexual scene," which meant interviews with hundreds, even thousands of sex partners, to find out who had the disease first and where he may have contracted it.

The article mentions the hardworking frontline doctors only cursorily—does not mention Dr. Dan William, Dr. Selma Dritz, or Dr. Mary Guinan at all. Shilts lets the doctors tell the AIDS story and keeps his own opinions at a minimum. That makes And the Band Played On the definitive history of AIDS. Who wants to disagree with so many doctors?

In one particularly egregious misrepresentation, Wikipedia says that Shilts described the "Before" of AIDs and the "After" of AIDS. "'Before', according to Shilts, was characterized by a care-free innocence;" but that is not what Shilts says! Shilts describes the "Before" as "innocence and excess, idealism and hubris." An Ancient Roman orgy had nothing on the gays of the 80s.

The tendency toward gay liberation meant civil disobediance, defying civil authority by doing just what they wanted to do. Shilts mentions several times: a sex act by gays is revolutionary! Sexually transmitted diseases are revolutionary! The memory of the government's crackdown on homosexual relations by arresting gays at the Stonewall Inn in New York City caused a riot. It set the tone for contentious relations between them and the government; but after a few years, when many gays had contracted AIDS, they blamed the government for its inaction. It takes some mental gymnastics to reverse course and hand the government the leadership role, to replace it enemical role at the last moment. It serves little purpose. Just beat the saddle, deflect responsibility onto someone else.

The government institutes unofficially personal standards of behavior as a means to protect the public and increase its consciousness about hygeine and health. The Gays defied the government's efforts, then turned around and blamed the government for the consequences of their actions anyway.

Some Gay activists recognized the consequences and tried to do something pro-active to reduce the frequency of AIDS. They encouraged the city of San Francisco to close the bathhouses. They had taken Dr. Conant's words to heart. The activists thought the initiative was the only responsible course. But the move proved divisive.

Dr. Mervyn Silverman, the Director of Public Health in San Francisco leaned toward closing the bathhouses unitl his decision reached the wider Gay public. Other Gay groups gave him hell for supporting closure. The activists tried to post warnings in the bathhouses not to engage in unprotected sex, but someone came in behind them and took them down again. Shilts recalled the division over the bathhouses:

Dr. Conant took (gay activist) Bill Kraus aside as the meeting was about to begin, and told Kraus that Silverman was backing away from closure.

"He doesn't have the courage," Kraus said.

Silverman said that he needed more time to think it over.

"When?" Kraus shouted. "We've been hearing this crap for years."

(W)ith the meeting disintergrating, Silverman raised his voice over the din. "Let's put it to a vote."

Kraus was stunned. . . . The room was split evenly between opponents and supporters.

Realistically, a government can do little without the consent of the governed. If the Gay activists in San Francisco cannot agree on a basic safety issue like the bathhouses, should the federal government step in and override the local goverment and close the bathhouses themselves? Present it as a clear and present danger to public health? And go through another Stonewall Inn type riot? That's not a likely scenario!