Walking in Step

Walking in Step

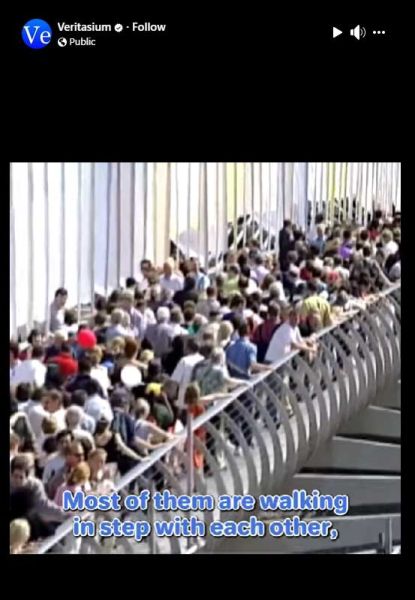

A blogger in London recorded this film-footage on his cell-phone for his Facebook page. It shows a real crowd of tourists crossing the Thames River over the Millenium Foot-bridge on its first day of operation. If you cross the foot-bridge from south to north, St. Paul'sCathedral will loom largely in the foreground. If you cross from north to south, you will see a replica of the old Globe Theatre in Stratford upon Avon, where William Shakespeare staged his plays.

The blogger noted something curious. As the crowd of tourists crossed the bridge, they walked as if in formation—left-right, left-right. The blogger mentions a phenomenon that I had never heard of, "crowd synchrony," to define the tourists' unconsciously stepping in unison. As they crossed over, they caused the bridge to sway from side to side.

But educated people should know already that we are like that. We not only follow a leader; we do it in unison—mimicking him, replicating his steps thousands of times. As our society rules itself more and more as a democracy, we focus more attention on a leader, and count on him to move us forward—not so much on ourselves moving forward with independent actions. Not surprisingly, the multitude of independent actions do not sway the metaphorical bridge as much.

The crowd-synchrony phenomenon makes me pessemistic about our ability to process information.

Our brain can turn to different devices to interpret our daily lives. We can respond dogmatically or with another kind of orientational input, from our leader for instance, but education and upbringing will hopefully give us the ability to define things cognitively, a.k.a. with a reasoning faculty.

Much of our orientation to life and problem-solving comes from our education, from our parents, or the unspoken parameters of the society. We can also respond with a quirky, individualized volition that goes by the name "inspiration," be it irrational inspiration, religious inspiration, with plain old intuition, or even counter-intuition.

In a democratic society, these stand-aparts don't think like the rest of us, and it makes us nervous. After a time, the stand-aparts learn to live, conscious of society's impress. Society gets jittery if the stand-aparts talk a lot, because we cannot count on them to give us standard, predictable answers. We even get nervous if stand-aparts ask a lot of questions.

In a democratic society, you learn to conform. Over time, you realize you have freed yourself from the need to explain anything. When someone asks you a question, you can hold him off with the standard, doctrinaire answer. He doesn't want to learn anything from you, anyway. He only wants to make sure you are thinking and saying the right things.

It worries me—so many Americans who talk about things in a group-think context—more worried about others perceiving them as different. They can't trouble themselves to figure out what they really believe about anything.