What Really Happened to the Class of '75? What really happens to any class. . .

What Really Happened to the Class of '75?

What really happens to any class. . .

Really, every college graduating class gets the same hype—new vistas, challenges, opportunities, and so on. Both the valedictorian and the guest speaker exhort the graduates to go out and conquer the world. They make you feel like crusaders, as game-changers. It works until you try to get a job, find a place to live, and all that. The first challenges, then, make you feel like something less than special. So many less-educated people hate uppety college students.

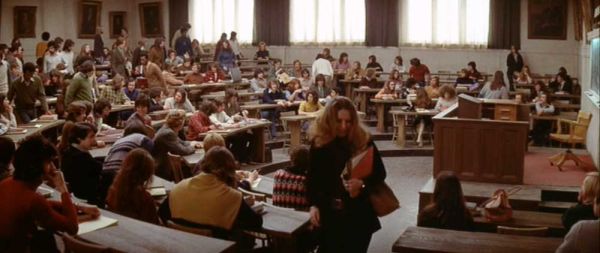

The Paper Chase film, 1973

There are not many quality films that describe the years Americans spend in college—that describe only the daily life of students, without some social message to overshadow it, without a tendentious moral theme to subordinate it, or nihilistic comedy with some sexual content, to laugh everything into oblivion.

Animal House movie, 1978

Maybe the grown-ups would just as soon forget they ever went to college, and hope to God no one finds out what they did there, or how badly they behaved. Others, like me, studied all day and half the night, and hated the monotony of it.

The Strawberry Statement movie, 1970

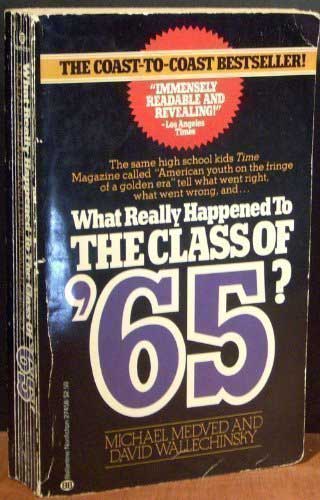

Michael Medved and David Wallichinsky published What Really Happened to the Class of '65 in 1976 about going to high school in California. No one has written anything comparable about college, unfortunately. By the time the authors published What Really Happened, most of them had already finished college, and they commented on it as much as they did their experiences in high school.

The authors conducted interviews with their former classmates, and their classmates' recollections make up the bulk of the text—which boy canoodled with which girl, how their dejected rivals felt about being stood up, the students' extracurricular interests, slowly developing career interests, drug interests, arrests, student protests, and so on. The classmates held nothing back. Many of them have since had second thoughts about giving away so much personal info, and have distanced themselves from the authors' plans for another edition of What Really Happened.

But their level of honesty impressed me; so in 2007, I published a novel in a similar vein, titled The Results of Polar Bear Research about college students on vacation—on vacation because students have lots of free and unstructured time, which gives them the opportunity to talk about themselves, review their lives, and plan for the future. Like the three movies I mention, Polar Bear takes place in the late-seventies, after the shock of the Vietnam War and the Oil Embargo have wound down, and people can start living normally again.

I had a lot of respect for my friends in college, as hard-working and dedicated. They also had more than a few doubts about the direction of the country, its leadership and policies, and the basic ethos behind it all. We had numerous conversations that went on late into the night. More than anything else, these other students made the college experience rewarding for me.

Whittaker Chambers, 1948, at a Congressional Hearing

They were "ernste Menschen," serious fellows, as Whittaker Chambers described his classmates at Columbia University in the early 1930s. They ate bag-lunches together in the school gym—most of them Jews whose parents had emigrated or fled from Eastern Europe. Chambers wrote:

They lived an intense, intellectual life, almost wholly apart from the life of the campus.

They were a cohesive group, bound together by a common flight from a common fear,

and a common poverty. . . . Not that they did not laugh. . . . Their humor was at times

highly intellectual. At other times, their humor was extremely earthy. . . .

Their seriousness was organic. It was something utterly new in my experience.

But Chambers does not touch on an aspect of college-life that I noticed, two-faced toadyism. I noticed it the first time during a planning-meeting. I had taken an anti-administration line to a social event occuring on campus; but another student, whom I considered a friend, disagreed with me, and piously took the administration-view. The administration figures who oversaw campus organizations breathed a sigh of relief and beamed approvingly at him.

But I realized there were some problems. My friend did not simply take an anti-establishment line on most issues, his overall manner could range from surly cynicism to open contempt and rebellion. But he had several things working against this stance. He was a scholarship student; he had career-goals that needed college-assistance to help him reach; and his parents exerted an influence in helping him reach his goals, in case his own volition failed him.

So, do you play by the rules, even if you hate the rules, and go along just to accomplish your goals? Just to oppose the Establishment is a fairly cheap display of willfulness. What do you have that can replace it, if you need a channel for advancing your career chances? It's bound to lead to a personal cynicism about your own character, and frustration if you need help from the Establishment, whom you disapprove of, to help you advance your goals.