Wolf and Wanger

Wolf, Reimann, and Wander

This article appeared in the Die Zeit newspaper during my visit to Germany in September and early October. It concerns three successul female writers in the former East Germany during the 1960s: Christa Wolf, Brigitte Reimann, and Maxie Wander. The photograph shows the crowded lunchroom at the factory where Brigitte Reimann worked, making charcoal briquettes. Not exactly the setting for a famous writer, where you would expect to see a nice desk and walls lined with books.

Maxie Wander also took a job in a factory, then as an office secretary, and finally writing scripts for radio programs. They accepted their role in East Germany, to define the lives of women in the new Socialist Germany, and to give women a sense of orientation, and to contribute to the collective goals of the East German nation. Of the three, only Christa Wolf lived long enough to see East Germany's collapse and its assimilation into the reunified nation.

As true-believers in Socialist Germany, many would have preferred it to remain independent. I wish it had remained independent too, since its existence was an everyday slap in the face for their idea of a socialist paradise. We need someone to represent that economic and philosophical pole somewhere in the world, so that we can see socialism in action, laboring against human nature.

Wolf, Reimann, and Wander pursued literary careers through East German channels. However you define former East Germany—as Marxist (not preferred), as Communist (not often used), or as Socialist (preferred), the government of East Germany defined itself as a democratic republic, which struck me as ridiculous.

Its border-guards shot would-be escapees. Private citizens could not own anything. The publishing industry, literary agents, and so on—all of that stuff belonged to the government. Publishing anything meant getting the blessing of the bureaucrats that censored all published material. So in reality, any published material reflected their uncreative mindset, not the people who wrote it.

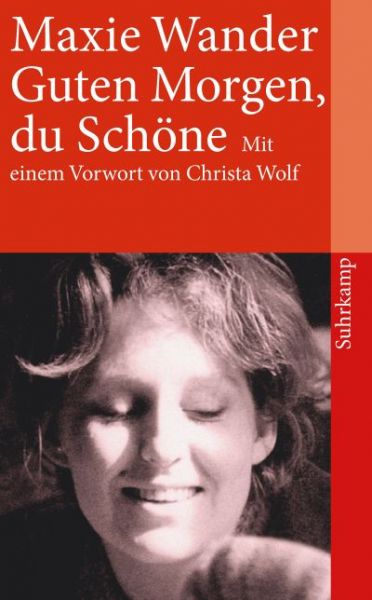

With a Soviet blessing, Maxie Wander published Guten Morgen, du Schöne (Good morning, my darling) in 1977, perhaps the most famous work of any East German writer. She created a style called Protokolliteratur, meaning written like a documentary. Wander did not structure the book as straight interviews but in conjunction with her own reportage on the nineteen women. She interviewed nineteen women of various ages and backgrounds about their daily lives.

The women did not say anything about the Berlin Wall, the militarized society, or the frequent incarcertations and blacklists, and they would hardly report about the West German TV programs that they secretly watched, but they did talk at length let the about diversity, sexism, and racism—famous left-wing leitmotifs in every country. That's very interesting!

The Zeit article states that Wolf, Reimann, and Wander concerned themselves with "ihre Staatstreue unter beweis zu stellen," (proving their loyalty) and "Selbstverwirklichung und Selbstermächtigung" (realizing their potential and empowering themselves). To think that intelligent, literary people can deceive themselves this way—gaining selfhood through Marxism. Karl Marx, the proponent of the anti-ego society, would have disapproved. It is alien to me, but Eric Hoffer wrote "by exchanging a self-centered for a self-less life, we gain enormously in self-esteem."

No matter the character of a society, dictatorial or free, a percentage of people in every society will do what it takes to succeed; and that presents a problem for freedom-lovers. In a free society, young guys will establish their own businesses in a college dorm-room, or the family garage. They will go to venture-capitalists and pitch the idea for a new company. They will get support from a capitalist, who will invest in the future company, in exchange for a share of the ownership. It happens all the time in a freedom-loving society.

But some people will know how to rise through the ranks of a dictatorial society, by stepping on the heads of their colleagues, by ingratiating themselves to their superiors, and really by selling their souls to the devil. That too, unfortunately, happens all the time. Just think of all the aspiring head-stompers who flourished in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. But the risk of such people rising in the bureaucratic ranks plagues every society.

Creative-writing worth its salt does not defer to anyone. It defines itself by the creator's own value-system, which may have religious parameters, cater to the accepted-beliefs of the society, or pull from the spectrum of opinions. Conversely, a writer may also influence or even change the society's accepted beliefs. Basically, creative-writing only exists in a freedom-loving environment, with a constitution that protects creative writers from government harassment, resident moralizers, and enforcers of public opinion.

Creative-writing does not have to actively dissent to anything. Its position as a dissenting voice can just as easily result from the way others in the culture react to it. With freedom of expression, I can write whatever the hell I want. No one has to buy my literary products. Literary vendors don't have to display them, but I can sell them myself and keep whatever money I get for them.

Creative-writing can only exist within private spaces. Those spaces allow us to freewheel inside our imagination, to create characters and plots from literary dust; but if we have to follow a doctrinal or thematic guideline, it turns us into literary sycophants. That may explains why so many successful writers go to pot. No one wants to consciously be a kiss-ass.