Working Overtime in Germany

Working Overtime in Germany

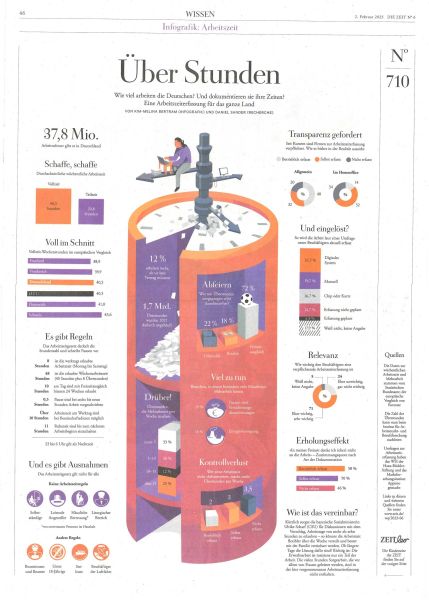

The German newspaper Die Zeit ran an interesting article in its February 2nd edition, titled "Über Stunden," about working overtime in Germany. The article by Kim-Melina Bertram and Daniel Sander contains just a little text. It consists mostly of charts pertaining to the average German's work-week, whether he works full-time or part-time, at home or in an office, how closely his employer monitors his hours, and how much he actually puts in each week. Sticklers for uniformity, the average German works 40.5 hours--right at center of the European average. Critics judge the 40-hour work-week too long and push for a 38-hour week. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the fiscally healthiest nations in Europe, Austria and Switzerland also have the longest work-weeks.

"Es gibt Regeln," write the authors: There are work-rules, based on the Arbeitszeitgesetz, or federal law regarding an employee's work-week. The weekly limit, or "erlaubte Arbeitszeit," Monday through Saturday, is forty hours, plus eight hours overtime. When workers go over that limit, they can take more time off the following week. In a poll, the workers admitted they benefit from the "Erholungseffekt," of having more time away from their jobs.The Arbeitszeitgesetz also stipulates that the workers should enjoy their "Ruhezeit," from 11:00 pm until 6:00 am.

Farther down in the left-hand corner, a less conspicuous chart refers to the "Ausnahmen," exceptions to the rules. The Arbeitszeitgesetz allows a few employed groups to waive the rules, among them the "Selbständige," or self-employed. That the self-employed do not fuss much about their working-hours does not surprise me. My father, for instance, was self-employed. He typically worked Saturday mornings until noon. Every evening, he scanned the want-ads and read through business journals until bed-time, and then woke up around six to read some more. He enjoyed work, he loved making money and never complained about working too long. Having grown up in the Great Depression, every quarter and half-dollar looked as big as the moon to him.

The next group in the list of "Exceptions" is the "Leitende Angestellte," the leadership of the business, its supervisors and executive staff. They have too much responsibility for the business to worry about the hours they have to put in. They tend to "bust-ass" anyway, as the ticket to a promotion. Nothing impresses their superiors like personal investment in the company.

Relegating the "Exceptions" chart to a less-visible place in the bottom left suggests that the authors Bertram and Sander care much more for the wage-earners and salaried workers than for the leadership or the self-employed. They care that the bosses should pay their workers fairly and not work them too hard. The idea that some people just like to work, make money, and advance in an organization occurs to them only perfunctorily.

The authors really take a socialist position on work and workers. Cultivating an us-against-them adversarial relationship of workers against the bosses completely overlooks the opportunities allowed in a free society, that it encourages advancement, making money, investing as the ticket to improve one's condition, and the privilege of starting one's own enterprise.

Native Americans may have a negative attitude toward the many options, but the reality of a free society is not lost on the immigrants. They enjoy working, making money, and they own a disproportionate percentage of American businesses--hotels, restaurants, and convenience stores. Their enthusiasm and prosperity has swamped the Natives.