What Really Works . . .

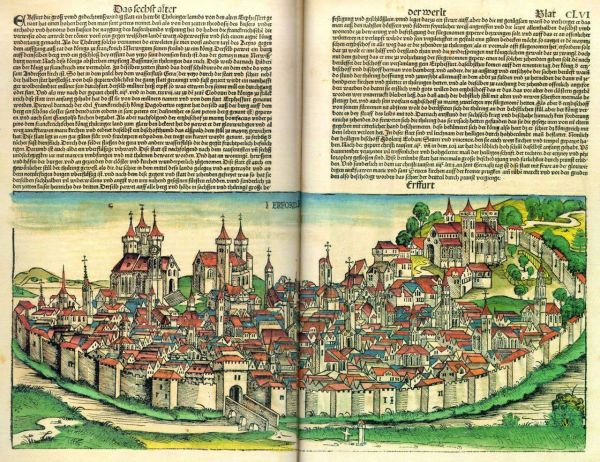

I can remember reading a history about my great-great-grandfather's hometown in Germany, named Erfurt. In the 11th century, a regional battle raged in Erfurt. Besides losing the battle, a fire resulted in the destruction of most of the city. The regional archbishop took responsibility for the rebuilding of the town and providing for its future; so he had to make policy changes to strengthen it.

First, he wanted to increase Erfurt's commerce, to put it on a stronger financial footing. He offered parcels of land to Erfurt's citizens. They could do what they wanted with the land; they only had to pay a tax to maintain their leases. Some citizens planted orchards; others wove baskets; still others worked in metal, glass, wood, or leather for saddle-makers, boot-makers, and upholsterers.

As the business base of the city grew stronger, the archbishop collected more tax revenue, which enabled him to erect a wall that surrounded Erfurt and protected it from marauders and vandals. As a result, more people wanted to move there for protection and a commercial network. When the archbishop ran out of parcels of land, he built a second wall to encompass more space.

In 1998, archeologists probing the site of a demolished building found a real treasure—jars full of money! They counted at least three hundred silver coins dating from the 14th century, called Gros Tournois. Many cities minted the Gros Tournois. Its uniform size and weight assured its acceptance across Europe. The Gros Tournois in the Erfurt treasure were minted in other German cities, in France, or in the Low Countries. That the coins travelled so far, reveals the strength and reach of Erfurt's trading ties.

In this same cache, the archeologists also found numerous items of jewellry: necklaces, bracelets, brooches,and ornate pins to fasten cloaks and scarves. The office of the archbishop even published warnings against citizens wearing too much expensive jewellry and risking violence to themselves from a street-robbery.

All of this historical information leads to one inescapable conclusion, that if political leaders want to create wealth in their domains, they have to enable private, independent commerce. Nothing else works as well. Commerce doesn't just create wealth, It enables the empowerment of an independent and networked leadership class. Commerce cultivates a pro-active, informed leadership mentality that initiates and responds to change.

At this time in history, political dissent in Erfurt did not exist. What the archbishop wanted, he got, no questions asked. Fortunately, his concept of survival involved the empowerment of Erfurt's citizens through commercial advancement. He allowed citizens to grow wealthy and let them to cultivate commercial relationships with other cities and nations, while the archbishop himself sat in a sort of heaven and held the strings. (borrowed from Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, by John leCarré)

If Erfurt had had a modern left-wing orientation to governing, it would have encouraged creating organizations tied to government- support, and it would have announced its intentions as modern left-wing groups do, using terms like "compassion", "community", equality, and inclusiveness; but leftists never talk so much about an independent citizenry or its empowerment through wealth-creation.

The Left's neglecting support for empowerment through independence suggests a lack of tolerance for it, or for the dissent likely to emerge from it. The Left may tout "diversity" as a defining quality, but its orientation suggests that the government will initiate diversity on its own terms, as the center of activity, which will necessarily limit its policy options.

Two such clashing cultures mix about as well as cats and dogs, or Jews and Nazis. Their defining qualities permit little inclusivity, except by coercion. For one thing, the risk-taking inherent in the commercial culture and the prospect of many losers among the winners frightens the compassion-based, control-oriented policies of the Left, who would attempt to marginalize risk-taking.