The Truth About Ruins

Seeing a building in ruins gives me the blues. From 1989 until 1991, I lived off and on in England and saw many ruins. When I started writing full-time in 2002, I wrote a short story about it, titled "The Truth About Ruins". The narrator remembers his honeymoon, when he toured England with his new bride and visited several ancient ruins. The scant information on their original appearance frustrated him. He can't see the purpose of leaving them in a ruinous state. It denies the ruins a sense of purpose or identity--just mounds of stone and mortar.

You can find gutted ruins in every city in England, down to remote villages, which consist of little more than naked, roofless, worn columns and broken masonry-walls standing no more than six to eight feet. Some of the ruins have stood in this condition for five hundred years or more. I still feel ambivalently toward ancient ruins.

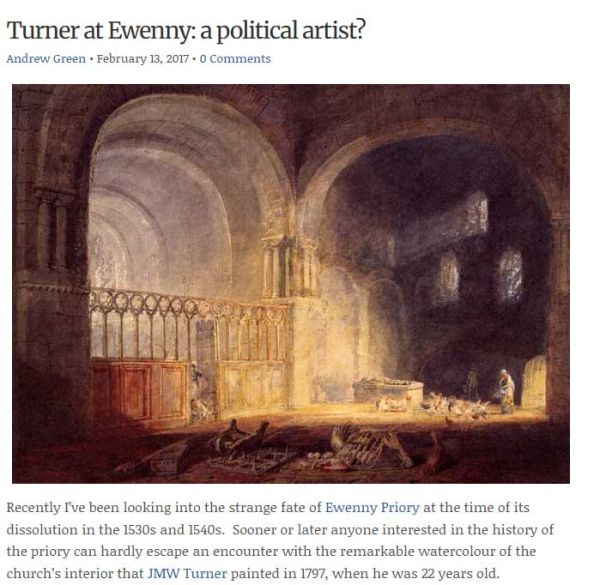

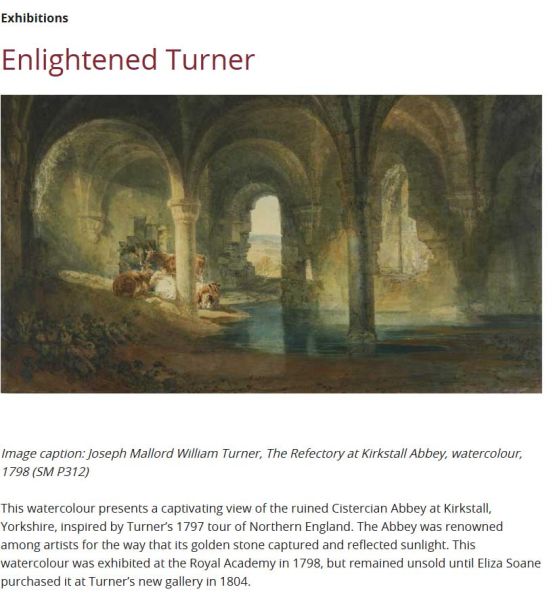

The 18th century painter J. M. W. Turner thought enough of the ruins to paint them. He painted the ruins of Ewenny Priory in South Wales and Kirkstall Abbey in Yorkshire—chickens in Ewenny and cattle in Kirkstall, a terrible comedown for such noble Norman buildings. Turner had to travel the length of the British Isles to do this—a distance of 170 miles! Quite a feat, in those days.

I suspect the residents of American rust-belt cities like Detroit and Gary see their modern ruins as an unmitigated blight on their prospects and a psychological downer; but archeologists in England tell us to leave them as they are. Archeologists say don't rebuild the ruins. Don't even repair them when they start to cave in, because the ruins give a place a historical reference, even if they do little more than chronicle the collapse of a civilization.

The experts say a ruin gives a place its historical or architectual perspective. To me, ruins don't tell the story of a place any better than a skeleton tells the story of a man. Ruins barely describe what a building originally looked like. You have to rely on contemporary illustrations to see them in their splendor; so you leave the ruins with regret over how violent and destructive history can be.

In earlier times, after all, if an important building suffered damage, the local authorities repaired it. In old buildings, you see a stone wall patched with bricks. If a building was too far gone, the local peasantry served as architectural scavengers. They needed the building materials for new buildings; so the scavengers recycled the ruins whatever they could use, so that little is left of them.

After the Romans left England, for instance, the Anglo-Saxon locals recycled the peculiar Roman-style bricks to build churches. You can't miss how long and thin they are. You can even find stones with Latin inscriptions on them, left by the Romans, recycled from foundations like Hadrian's Wall, that protected England's northern border from the Scots and Picts on the other side. The present-day Hadrian's Wall is hardly a nubbin of its original size. Its 73-mile course looks forlorn in the remote, wind-swept terrain.

The truth about ruins is that, as nations evolve, the structure, philosophy, and intentionality of the society evolve as well. Church-oriented societies evolve into secular monarchies, then constitutional republics, if they are lucky—ruthless dictatorships if they are not lucky. Not only does this evolution negate the charter of the older society, it negates the old society in its material form, principally its buildings.

After all, seeing the grandeur of the old buildings makes the citizens nostalgic for the Old Order. The people admire the established stateliness and dignity of the Old and wish to have it return. The leaders of the New Order cannot allow that and will destroy the memory of the Old to keep the public from thinking about it, even if the new buildings are brutally tasteless.